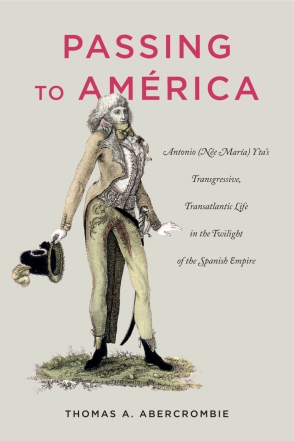

Passing to América

Antonio (Née María) Yta’s Transgressive, Transatlantic Life in the Twilight of the Spanish Empire

Thomas A. Abercrombie

Passing to América

Antonio (Née María) Yta’s Transgressive, Transatlantic Life in the Twilight of the Spanish Empire

Thomas A. Abercrombie

“Abercrombie’s thrilling account of the life of Don Antonio Yta follows the surprising twists and turns of a nun in a Spanish convent turned male bishop's page, governor's servant, and town administrator in Italy and the Americas. With depth and meticulousness, Passing to América reveals the possibilities and limitations that race and gender afforded individuals who, like Don Antonio, sought to pass as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth.”

- Unlocked

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

An Open Access edition of Passing to América is available through PSU Press Unlocked. To access this free electronic edition click here. Print editions are also available.

Passing to América is at once a historical biography and an in-depth examination of the sex/gender complex in an era before “gender” had been divorced from “sex.” The book presents readers with the original court docket, including Don Antonio’s extended confession, in which he tells his life story, and the equally extraordinary biographical sketch offered by Felipa Ybañez of her “son María,” both in English translation and the original Spanish. Thomas A. Abercrombie’s analysis not only grapples with how to understand the sex/gender system within the Spanish Atlantic empire at the turn of the nineteenth century but also explores what Antonio/María and contemporaries can teach us about the complexities of the relationship between sex and gender today.

Passing to América brings to light a previously obscure case of gender transgression and puts Don Antonio’s life into its social and historical context in order to explore the meaning of “trans” identity in Spain and its American colonies. This accessible and intriguing study provides new insight into historical and contemporary gender construction that will interest students and scholars of gender studies and colonial Spanish literature and history.

This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of New York University. Learn more at the TOME website: openmonographs.org.

“Abercrombie’s thrilling account of the life of Don Antonio Yta follows the surprising twists and turns of a nun in a Spanish convent turned male bishop's page, governor's servant, and town administrator in Italy and the Americas. With depth and meticulousness, Passing to América reveals the possibilities and limitations that race and gender afforded individuals who, like Don Antonio, sought to pass as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth.”

“Approaching the story of Don Antonio Yta, and the María he was before, is bound to pull us into a thicket of contemporary debates about gender and sexual identities. Thomas Abercrombie is a skillful guide, letting the reader get tangled where necessary by including primary sources and playing in ambiguities but also pointing to ways out. Particularly impressive is how Abercrombie places gender and sexual practices within a context of multiple other factors that impacted the lives of Don Antonio and María, from Spanish peninsular class status to immigrant experiences in the New World during the apogee of an Enlightenment science of self and other.”

“Abercrombie relays the story of Antonio (née María) Yta's movements from Spain to Bolivia, and from seeming woman to apparent man, with remarkable detail and insight gleaned from the twenty years of research whose fruits are so evident in these pages. This book makes a strong contribution to transgender studies historical scholarship, and it supplies the best case study of the complexities of colonial gender in the Americas since the fabled tale of the Lieutenant Nun, Antonio (née Catalina) de Erauso.”

“Thomas Abercrombie’s Passing to América is the surprising story of how the materiality of clothing and the deportment associated with status and honor, rather than the body itself, defined sex in the Spanish Monarchy in the Age of Revolutions. Abercrombie brilliantly uses this story of Don Antonio Yta to challenge current interpretations of the primacy of the body in trans-gender identity.”

“Indeed, Tom’s book crosses many disciplinary frontiers, for Passing to América is historical biography at its most intriguing, but also an in-depth look at the sex-gender complex at a time in history when both sex and gender were understood and performed very differently. Tom Abercrombie’s extraordinary life work has created its own pathway of memory and knowledge, for which we all can be profoundly grateful.”

“This book is highly recommended for courses in the history of global sexuality and should be required reading for understanding gendered history in Latin America.”

Thomas A. Abercrombie was Associate Professor of Anthropology and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University and the author of Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History Among an Andean People.

From the Introduction, “Exposure”

Report of a Scandal

“I report to your mercy the strangest case to have happened since the beginning of the world, and it is that two women married each other four years and some months ago, which I will relate in detail for your amazement and diversion, and it is as follows” (Beruti 1946, fol. 188). Thus began a letter written by Dr. Mariano Taborga Contreras to a high-placed friend in the viceregal capital of Buenos Aires, reporting breathlessly on the revelations in his courtroom just a week before on October 7, 1803 (full text at the Passing to América [PTA] website, https://wp.nyu.edu/passingtoamerica/). This was quite possibly his first case as legal adviser (a job he did not yet formally hold, though he acted as though he did) to the president of the Audiencia de Charcas, a regional appeals court of the Spanish Crown, located in La Plata, the capital city in the Andean highlands of Spain’s South American realms. Since the case was ongoing, sending the letter was an indiscretion. But what lawyer could have resisted the temptation to repeat its details to a confidant? Let us continue with the details of Taborga’s letter, written from the nearby mining center, the Villa de Potosí.

October 15, 1803:

On the seventh of the current month a woman presented herself to me who had just arrived in company of the mails from Cochabamba, named Doña Martina Vilvado y Balverde, presenting me with a petition against her husband, Don AntonioYta, explaining that he is native of the kingdoms of Spain and that she has been married to him for over four years and that they were married in this villa [Potosí] with license from V. [Don Francisco de Paula Sanz?] for being from Spain [ultramarino] and because he had not carried out the duties of matrimony, protesting [that he had made] a vow of chastity and other silliness, and having observed that he always urinated in a basin, always wore underpants, menstruated, and other observations, such as swollen breasts, etc., were revealed.

And for constantly disguising herself as a man and everything else, I had the accused searched for. Placed into my presence I observed a smallish and chubby man, around forty years old, and, taking his confession, I discovered that he was named Doña María Leocadia de Yta, native of Colmenar de Oreja, seven leagues from Madrid, who had come without license to this kingdom, having embarked in Málaga. She had been in a convent of nuns at age fourteen, and because she fell in love with the other nuns, they threw her out of there; she went to confess, and the priest told her that it would be best to go to Rome. /188v/ She left a note for her parents and, wearing her natural clothing, made the following voyages: from Madrid to Valencia, from there to Barcelona; in that port she embarked on a mail ship for Genoa, in the company of some Italian actors from that city. She continued her voyage with them as far as Civitavecchia and, continuing with the Italians, by land to Rome, where she confessed, and the penitentiary, who was a Spanish Franciscan friar, told her to return on the third day. Doing so, she received absolution, and for penitence [she had] to climb the Jerusalem steps thirty times, to whip herself every Friday during one year, to avoid hearing mass in nuns’ convents, and to put on men’s clothing. Replying to the priest, the penitent asked how she could return to her home wearing such clothing. [He replied] that it was necessary to do what the Holy Father commanded but without returning to her home country. For that reason she dressed as a man and remained in Rome awhile. She returned to Civitavecchia, Genoa, and embarked there for Barcelona, and hence for Málaga, and in that port for Montevideo. She was in Buenos Aires for two or three years in the house of Lord Azamor, bishop of that city until his death, and then she determined to come to Peru. This side of Lujan she had the misfortune of breaking a leg and was detained for four months. Finally, she reached Potosí, where for some time she stayed in the house of the lord Sanz. There she dallied with love [trato de amores] and was living/sleeping/involved with [amancebado con] the above-mentioned Doña Martina Vilvado. Later they married. Afterward, she lived with her in comfort that was facilitated to them in Mojos, to which they both went, and, having returned, Vilvado was in her hometown of Cochabamba; and three or four months ago, Doña María Leocadia came here to litigate the salary owed to [Don Antonio] for serving as administrator. In all this time, both attested to the good treatment that he gave her [Martina], in which insofar as possible she lacked nothing for her decency, but she was irritated with his frequent jealousy over her. In my presence the said María Leocadia was examined, because she had said before the scribe and titular physician and surgeon that she had a man’s parts. But it is all falsehood, and she is a woman like all the others, and if she shows herself to be very bold, she shows no other signs of being male. What is certain is that the whole story of her declaration is a web of lies. She is a woman of many secrets [or back rooms, or closets], sick in the head, who hates her [woman’s] clothing, because she is given over to a rascal’s life. I have her alone in a cell. We’ll see how it turns out. To be continued. (Beruti 1946, fol. 188r–v; my translation)

Considering Don Antonio, in His Time and Place

What a scandal! Don Antonio Yta was truly a self-made man or, rather, a woman living disguised as a man, and with an astounding backstory. Perhaps it was a web of lies, made even more scandalous by his very success at passing as a man, deceiving powerful men for a decade and a wife for more than four years of marriage. One week into the case and Taborga had already reached that firm conclusion, having seen with his own eyes what looked like a female body and having heard Don Antonio confess to having been raised as Doña María Leocadia Yta (henceforward, Doña María). Don Antonio had insisted that he had a functional male member in the act, but Taborga’s eyes told him that it was nothing but a lie. What was true, Taborga concluded, was that he was faced with a woman who loved women but hated being one and who preferred the adventurous life of a rascal—a social climber using devious means to obtain better fortune, in this case, a wife and a man’s career.

Other jurists involved in the case were less certain than Taborga. Some took Don Antonio at his word and decided that he was a hermaphrodite. Even the physicians called in for the examination left a bit of uncertainty in their report, allowing that though what Don Antonio said was a penis was in fact an ordinary clitoris, they had not seen it in the state of arousal mentioned by Don Antonio. His legal standing as the man and husband and his continued self-presentation as a man in the weeks and months locked in jail as the case slowly progressed led some (his attorneys, some judges, and his jailors) to continue to refer to him, Don Antonio, while others stuck with her, Doña María, and a few vacillated in attributing name and sex to the prisoner.

What was going on here? What kind of person was this Don Antonio? Was he really a she, as Taborga concluded? Or was his sex ambiguous, with both male and female characteristics? Given that he was apparently raised as a girl and lived as a woman for more than twenty years before becoming a man, how was “she” able to learn how to adequately inhabit a man’s clothing and social roles and at the same time conceal and keep secret the female (or ambiguous, “hermaphrodite,” or intersexed) body beneath that clothing? What kinds of labors were required of Don Antonio to sustain his “imposture of sex,” as his accusers called his practices? What motivated this change of sex? Was marrying Doña Martina a cover to be able to live as a man? Was it a “cover” to be able to love women and to marry one without being censured (as had happened when Don Antonio was still Doña María)? Or was it some combination of these things? How could his wife have taken more than four years to figure out that her husband was a woman in disguise? Finally, what explains the legal system’s apparent inability to definitively determine his sex, to classify his sexual practices, or to name his crime? This book aims to reveal Don Antonio’s story in all its complexity, placing it fully into its historical and cultural context. Such a project is possible in this case (unlike many others sharing some of its aspects) because Don Antonio told at some length his own life story, later joined by a biographical sketch sent by his mother seeking to help him get out of trouble. To begin to understand Don Antonio, and not only to grasp what others thought of him but how he understood himself, we must read these sources very closely. For that reason the essential texts are provided in appendixes to this book.

It has been said that the past is a foreign country (Lowenthal 1999). That is why serious effort is required to understand what kind of girl and young woman Doña María had been and what kind of man Don Antonio became. It takes effort, as well, to understand Doña Martina, the vexed wife, and the rest of the figures in the case. To unpack what was happening in that courtroom in La Plata, we must dig into the “taken for granted” of life in that time and place. It might seem that the central question here is rather straightforward: was he a man or a woman? But for his contemporaries, it turns out that (apart from Taborga), looking at his genitals was not enough to fully clarify even Don Antonio’s sex. Can we do better?

As we shall see, determining another’s sex is not in the least bit straightforward. Every scientific advance today seems only to complicate the matter, though some, then as now, prefer a cut-and-dried, no-complications world, where only binaries can exist, each granted “natural” forms of expression. Taborga was one of those. For him, Don Antonio was a masquerade, a deception carried out by the woman Doña María Even if that were the case (and not everyone involved was as certain as Taborga), understanding how Doña María pulled off such a deception requires us to know about much more than just his or her genitals. For then, as now, there was not just one way to be a man or a woman. Doña María, and then Don Antonio, had to become expert in performing very specific kinds of woman and man, bound by cultural patterns quite different than our own. To understand Don Antonio requires us to know them too. Moreover, we must answer the question of how Doña María learned how, during her first twenty-one years as specific kinds of girl and woman, to convincingly be a specific kind of man, a transformation pulled off in a very short space of time.

The task is not easy, because the moment that Don Antonio’s life was committed to paper occurred more than two centuries ago, in another time and another place. Doña María’s adventures traversed Spain and major cities of the Mediterranean, while Don Antonio’s passages swept him across the Atlantic into América. That is what Spaniards and their Creole descendants in the “Indies” or the “New World” called the American possessions of the Spanish Empire by the mid-eighteenth century, those earlier terms having fallen into disuse. The vast Spanish Empire, which had reached its apogee as a world power two centuries before, was now in decline, while the upstart British Empire had just lost its thirteen colonies on a small stretch of northeastern North America, in the nascent United States of America. No such thing as América Latina, “Latin America,” yet existed in the minds of the inhabitants of Spain’s América, and they bristled at the theft of their continent’s name by the fledgling Anglo-American state. “América” serves to inflect the continent’s name with the point of view of its Spanish-speaking majority.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.