Making Magic in Elizabethan England

Two Early Modern Vernacular Books of Magic

Edited by Frank Klaassen

Making Magic in Elizabethan England

Two Early Modern Vernacular Books of Magic

Edited by Frank Klaassen

“Each of the two very different sixteenth-century texts edited here offers a panoramic view into its compiler’s world; liberally enhanced with arcane diagrams, the texts are usefully contextualized by the notes and ancillary materials Klaassen provides. In addition to the general introduction, which is both learned and comfortably reader-friendly, each magic text has an individual introduction offering a finely tuned reading sensitive to the layering of sources and the complexity of the compiler's stance. Like all Klaassen’s work, this book is meant to be enjoyed.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

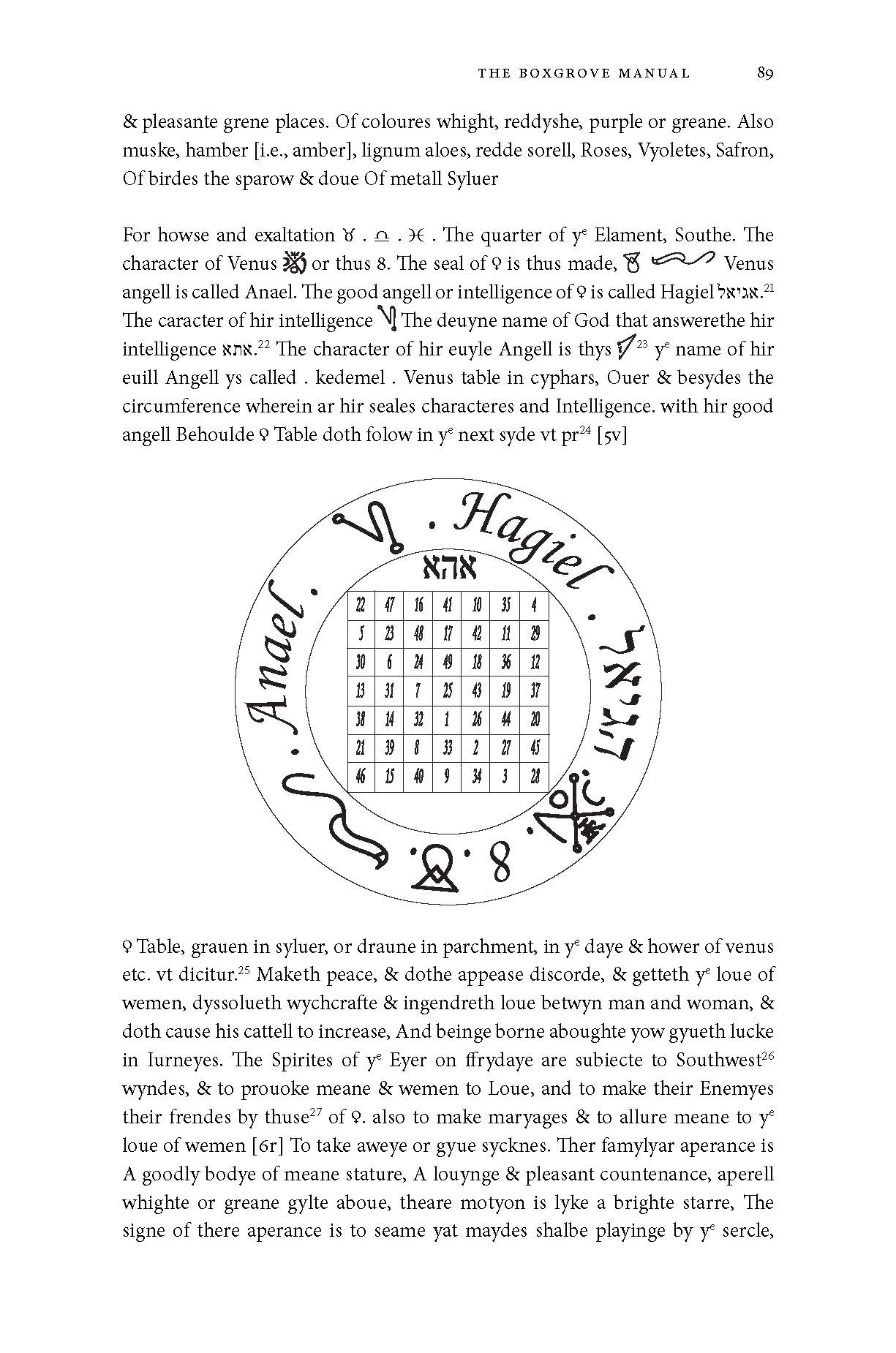

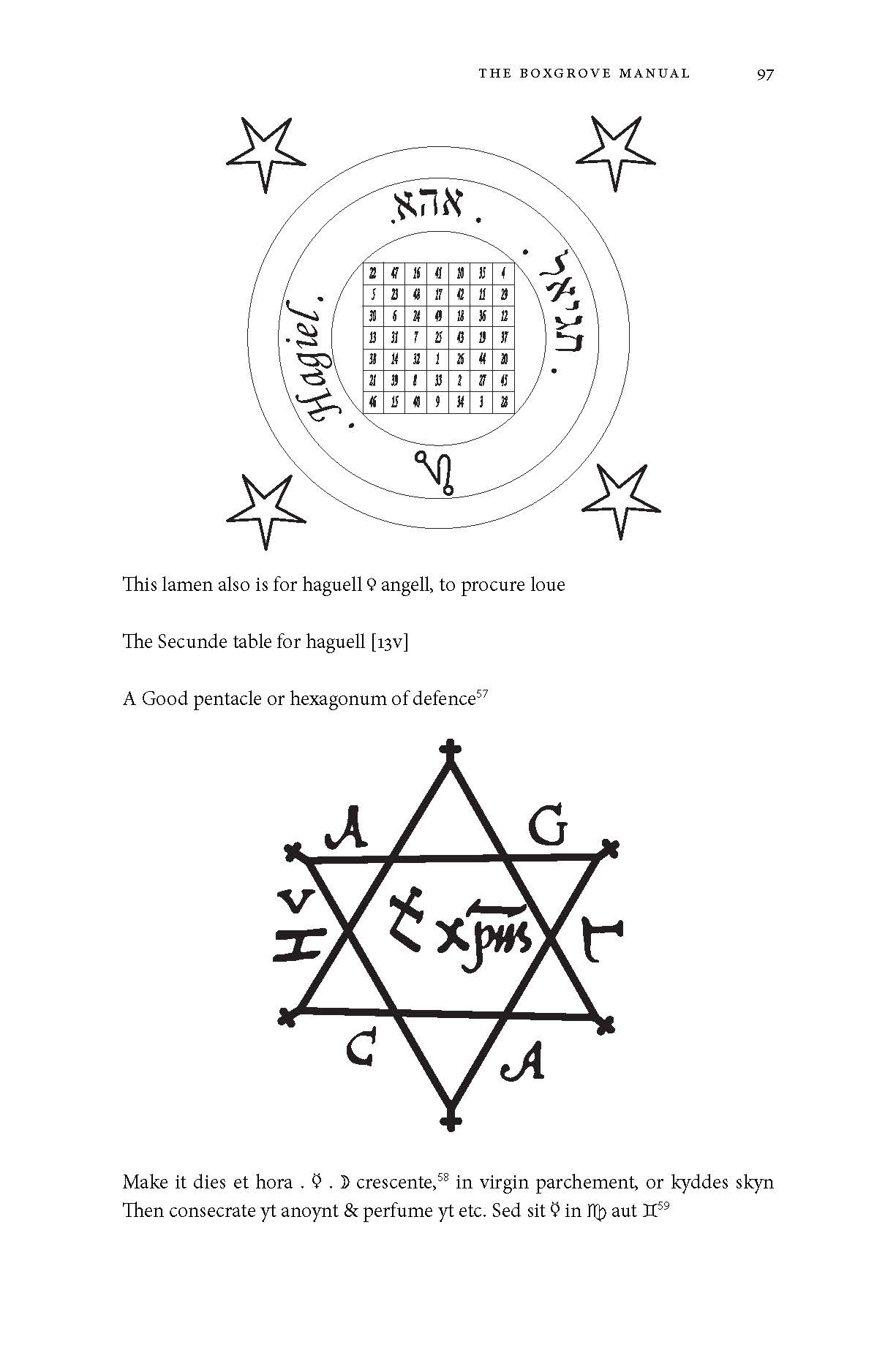

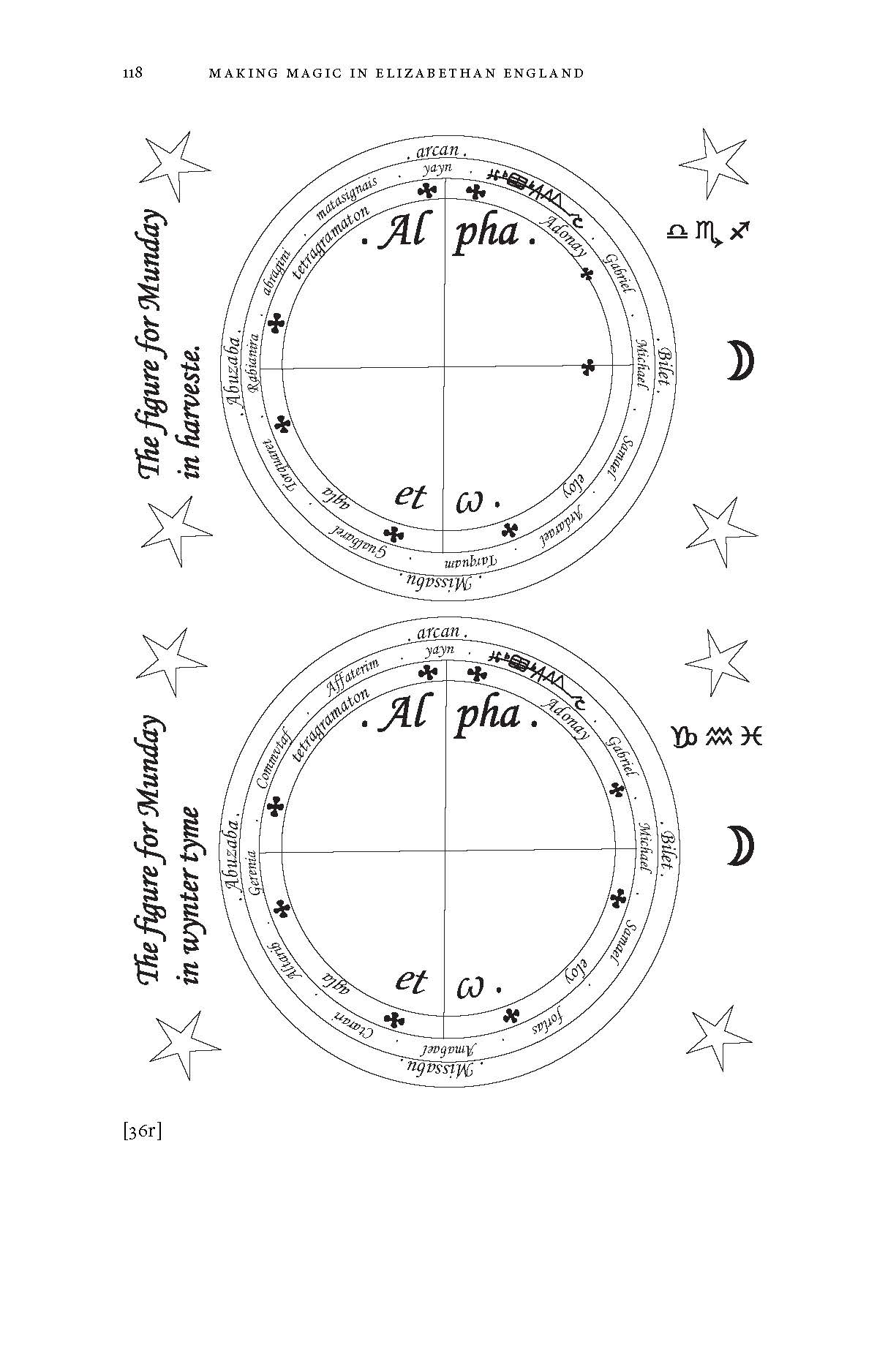

The Boxgrove Manual is a work of learned ritual magic that synthesizes material from Henry Cornelius Agrippa, the Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy, Heptameron, and various medieval conjuring works. The Antiphoner Notebook concerns the common magic of treasure hunting, healing, and protection, blending medieval conjuring and charm literature with materials drawn from Reginald Scot’s famous anti-magic work, Discoverie of Witchcraft. Klaassen painstakingly traces how the scribes who created these two manuscripts adapted and transformed their original sources. In so doing, he demonstrates the varied and subtle ways in which the Renaissance, the Reformation, new currents in science, the birth of printing, and vernacularization changed the practice of magic.

Illuminating the processes by which two sixteenth-century English scribes went about making a book of magic, this volume provides insight into the wider intellectual culture surrounding the practice of magic in the early modern period.

“Each of the two very different sixteenth-century texts edited here offers a panoramic view into its compiler’s world; liberally enhanced with arcane diagrams, the texts are usefully contextualized by the notes and ancillary materials Klaassen provides. In addition to the general introduction, which is both learned and comfortably reader-friendly, each magic text has an individual introduction offering a finely tuned reading sensitive to the layering of sources and the complexity of the compiler's stance. Like all Klaassen’s work, this book is meant to be enjoyed.”

“Those studying the history of magic want not only to look at historical books of magic that were important to practitioners, but also to the contexts in which these books were produced, circulated, and held suspect. Frank Klaassen gives excellent access to both texts and context with this edition of two particularly fascinating books. The Antiphoner Notebook and the Boxgrove Manual were produced at roughly the time of Shakespeare, and the magicians who compiled them might well have served as models for one of his characters. This expertly produced volume will be of great interest to historians and to anyone interested in early modern English culture.”

“With this meticulous and readable edition, Klaassen excavates the world of early modern magic through a pair of grubby manuscripts. This is a perfect introduction to the history of magic.”

“Frank Klaassen’s welcome and lively edition of two Elizabethan magical manuscripts brings to a wider readership works that would otherwise be both arcane in their subject matter and hard to access in their physical form. This is valuable in itself, but Klaassen’s adept framing of the texts adds significantly to the usefulness of his book.”

“Klaassen has made a mark on the early modern study of magic already; with this scrupulously edited and well-contextualized and introduced document of hermetic and kabbalistic traditions of ritualistic magic, and of the writing on magic, he has expanded scholarship on magic and enriched both scholars’ and students’ understanding and appreciation of the ritualistic working of magic in further detail and within English and Continental thought and historiography.”

“This is a highly recommended reading for students and scholars of magic.”

Frank Klaassen is Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. His recent publications include the award-winning book The Transformations of Magic: Illicit Learned Magic in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance, also published by Penn State University Press.

Acknowledgments

List of Abbreviations

General Introduction: The Devil in the Details

The Antiphoner Notebook

Introduction

The Text

The Boxgrove Manual

Introduction

The Text

Appendixes

Bibliography

Index

General Introduction: The Devil in the Details

The most significant corpus of European magic manuscripts surviving from the early modern period, in terms of its influence on modern traditions, maybe even raw numbers, was produced in England. Occultists and historians of medieval magic looking for witnesses to earlier works have long recognized this fact, but historians of the early modern period have begun only in recent decades to pay closer attention to this considerable body of evidence as a whole and the complex culture of magic that produced it. In her effort to emphasize the centrality of hermetic and kabbalistic traditions, Frances Yates quietly overlooked this literature, which she regarded as the magic of a past age. She painted England as a stagnant intellectual backwater, which eventually took up the stylish continental trends in magic, beginning with John Dee, whom she represents as a great hermetic mage. Work on John Dee has freed him from this straightjacket, but in turn, he has come to dominate the study of early modern English magic. The incredible richness of his surviving works, their intellectual sophisticationand influence on modern magic, his intimate associations with the great monarchsand intellectuals of his day, and, perhaps most of all, the intriguing ambiguitiesand drama of his story have made him both compelling and also very much worthy of study. At the same time, these qualities make him unrepresentative of the culture of magic practice, most of which was pursued in less sophisticated ways and further from the halls of power. In fact, Dee’s magic itself was to a significant degree the product of an ambient culture of magic, one more accurately represented by the likes of his skryer, Edward Kelly, than Dee himself. Where scholars have tentatively dipped into the wider literature of practical magic it has tended to be tangential to their work on other projects. So it remains that not a great deal is known about this significant body of evidence and the intellectual world in which it was produced.

In opposition to the Enlightenment view of magic as a disappearing and therefore irrelevant relic of a superstitious past, Yates painted a picture of an attractive and intellectually sophisticated tradition of high magic that lay at the core of the Renaissance and the scientific revolution. This was critical to redeeming magic and establishing it as a legitimate topic for scholarly investigation. Understandably, later scholars of early modern magic have tended to follow her in this strategy and have shied away from a body of evidence that does not have this kind of sheen but is, in raw statistical terms, overwhelmingly more representative of sixteenth- century magic. They have also been legitimately leery of it. Until recently, little was known about the medieval traditions that fill sixteenth-century magic manuscripts. As a result, there has been no clear way to get a handle on this substantial library of texts: what aspects of the older traditions their scribes preserved, how they transformed them, and how their activities reflect the peculiar circumstances of the period. But this has changed.

In the past two decades scholars have made significant progress in coming to terms with the literature and intellectual culture of medieval learned magic. It is now possible to see that, although sixteenth- century scribes worked with a substantially medieval set of traditions, the story is not merely one of continuity. A good deal of subtle experimentation took place at this time in which we can see scribes conceptualizing magic on a basic level. The new trends in science and the religious upheavals of the period brought new perspectives to medieval traditions, including magic. These influences were compounded by the vernacularization and popularization of medieval learned magic, the reconfiguration and reframing of magic in the hands of renaissance intellectuals, and the increasing body of printed works on magic. All of these were clearly in the minds of scribes as they copied and reimagined the magic literature they had inherited. The result was not a coherent body of magic literature, much less one that changed in predictable ways. Whereas some scribes carefully preserved and duplicated earlier texts, others significantly transformed them. Some simplified; some experimented with new forms or synthesized old ones. Some preserved the Catholic elements; some carefully edited them out. In short, sixteenth- century England had its own distinctive, rich, and lively subculture of magic that we are now uniquely positioned to explore. And the devil, as it were, is in the details.

It is my contention that in these manuscripts of deceiving rogues and true believers, middlebrow conjurers and Latinate mages, as much as in the dizzying esoteric traditions of renaissance high magic, we may see the origins of modern European magic. This volume seeks to correct the imbalance in our understanding of sixteenth- century magic by exploring two manuscripts representative of this broad and largely unexplored body of evidence. The Antiphoner Notebook, written on blank parchment that once formed the margins of a large monastic manuscript, is preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. A late sixteenth- century scribe who was interested in magic, charms, and the old religion filled its pages with material from at least three sources: a medieval conjuring manual, one or more collections of medieval charms, and Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft. The Boxgrove Manual is an attempt by an English magician writing sometime after 1578 to synthesize at least two late medieval conjuring texts with two pseudonymous printed works on ritual magic and materials from the great Renaissance magus Henry Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim. It is now preserved in the British Library. While they certainly do not represent the entire spectrum of magic practice in late sixteenth- century England, these two texts evince many important dimensions of that period in the history of magic, in particular how two scribes went about assembling or making a book of magic. To do this the scribes did not simply copy from old books; they collected various sources, then weighed, adapted, and blended them for their own purposes. In turn, this process of scribal authorship reveals a good deal about their reading habits, motivations, and ideas, all of which were expressions of the social and intellectual upheavals of the sixteenth century and the wider intellectual culture of magic in the early modern period. Only by examining the manuscripts of contemporary magicians and by firmly situating the authors in their intellectual worlds—in the books they read and how they transformed them—may we begin to reframe our approach to magic in the early modern period.

Medieval Ritual Magic and Charms: Sources and Continuities

The texts in this volume derive material from two principal genres of medieval magic: charms and ritual magic. The Antiphoner Notebook contains examples of both, while the Boxgrove Manual draws solely on the latter. Knowing where these forms of magic came from can help us understand why they look the way they do, the ways they reflect continuity with their medieval sources, and ultimately the changes they underwent at the hands of their Elizabethan scribes and authors. Our discussion will begin with the tradition of ritual magic before turning briefly to charms.

The term “ritual magic” commonly designates practices involving lengthy ritual operations. Works in this genre written in the Latin West were based in significant measure on the Christian liturgy and framed in Christian terms but also drew in part on Hebraic and Arabic magic traditions. Although this form of magic generally requires the observance of astrological conditions, particularly the phases of the moon, planetary hours, and days of the week, the texts make clear that the most important elements are the preparatory ritual observances and the spiritual condition or character of the operator. For example, the magician must be a Christian in a state of grace (having confessed and taken communion and having avoided sources of corruption, such as sex, for a period of at least three days), be blameless in his comportment, with a clean body and clothes, and often have observed a lengthy regime of prayer, fasting, and religious devotion. European ritual magic also tends to seek direct experience of the numinous or the infusion of spiritual gifts. If the number of surviving manuscripts is any indication, the most significant premodern work of this genre was undoubtedly the Ars notoria, which sought the infusion of knowledge and spiritual gifts following the performance of complex rituals, prayers, and contemplative exercises. Other examples include the Liber iuratus Honorii, Clavicula Salomonis, Thesaurus spirituum, and Liber consecrationum, which were supplemented by a significant variety of anonymous texts. These works seek direct experience of spirits or the divine, although the purported nature of those spirits and the manner of approaching them varies somewhat. They situate their rituals in a variety of mythologies. Some trace their lineage to mythical medieval authors such as Honorius of Thebes, others to Old Testament figures like Adam or Solomon.

Scribes of ritual magic in the Latin West regularly adapted and transformed the magic books that they had inherited. In fact, the mythology of these texts encouraged this tendency by valorizing the role and agency of the practitioner. Works of ritual magic represented the great magician as a kind of divinely guided practitioner- editor whose long experience in magic was crucial to uncovering the truths in obscure and ancient magic books intended only for the chosen few. Numerous rituals reinforce these ideas by offering concourse with spirits for the express purpose of attaining information or guidance regarding the practice of magic. As they confronted these often fragmentary and difficult texts, it seems likely that many imagined themselves in the role of an elect inheritor and interpreter of primordial secrets. One of the byproducts of this culture was what Julien V.ron.se has called the author- magician, the practitioner who created new works of magic to which they attached their name. But this was only the most dramatic expression of a wider culture in which scribes actively took up the challenge of interpreting their obscure source texts, expanded and explicated them, and/or compiled their own new magic books from them. For example, scribes wrote explanatory additions to the original Ars notoria in order to make it more understandable, and later ones abbreviated and simplified it in various versions. Similarly, the fourteenth- century monk John of Morigny created a new system of intellectual magic based on the Ars notoria that he combined with Benedictine contemplative traditions and the affective Marian piety. The changes that scribes made to the texts were sometimes minor, but they were certainly regular, giving rise to a textually chaotic and shifting body of literature that reflects in fascinating ways the changing intellectual, religious, and social world around it. At the same time, until the latter decades of the fifteenth century the literature remained relatively coherent in its self- conception and form, particularly its heavy endorsement of, and reliance on, conventional religion. This general stability was in part assured by the stability of the intellectual and social environment in which it was transmitted.

Medieval ritual magic was generally the preserve of male clerics, both regular and secular, and also more broadly of those associated with the universities, who had adopted clerical sensibilities. Unsurprisingly, it reflects their worldview. The goals promised by the texts suggest a largely male audience, but more crucially the rules of operation uniformly assume male practitioners, ban undue concourse with women, and often specifically forbid revealing the secrets of magic to them. The procedures not only required Latinity, but the operations reflect an extensive knowledge of the liturgy difficult to perform by those not well versed in it. By demanding learning, a high level of self- control, fasting, sexual abstinence, regular participation in rites of the Church, knowledge of the liturgy, and homosocial surroundings, they not only made a virtue of the clerical lifestyle, but also turned it into a source of cosmic power. That the texts were written in Latin made them inaccessible to most people and tended to reinforce their claims to being high secrets fit only for the learned few. The rituals drew heavily from the liturgy and were represented as both holy and thoroughly Christian. In other words, despite being illicit and despite their promotion of some theologically problematic ideas, they tended simultaneously to reinforce the religious and intellectual status quo in significant ways.

During the course of the fifteenth century, however, the readership of these texts began to expand as scribes increasingly transmitted learned magic of various kinds into vernacular languages, placing it in the hands of people with different sensibilities and who did not have the language skills to understand the original Latin texts. This process accelerated considerably in the sixteenth century and a considerable body of vernacular ritual magic literature developed alongside the older Latin literature. New readers and transmitters of magic increasingly did not have university training or an extensive knowledge of the liturgy, were not the products or inhabitants of the same homosocial world as their predecessors, and did not lead even superficially clerical lives. Predictably the texts began to change. They tended to shed many of the complex liturgical elements in favor of greater simplicity. They also began to draw in elements from popular magic or to create new ones that did not reflect the sensibilities of the original medieval texts. This is particularly visible in this volume in the ritual magic sections of the Antiphoner Notebook, which are shorter and quite different from their medieval models. The scribe’s inability in Latin rendered some of the prayers and invocations nonsensical and also drove him to use Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft as a sourcebook. Scot not only provided translations of medieval texts but also collected vernacular material which had already been simplified and transformed. A parallel process is also visible in the tradition of books of secrets in which Latinate scribes became cultural brokers providing materials to a non- Latinate audience, while simultaneously systematizing popular knowledge in written form. As we shall see, the Boxgrove Manual also translated and digested magic from a variety of medieval and early modern Latin sources. Although medieval in conception it incorporated materials from sixteenth- century printed works on magic, excised Catholic elements, and privatized the magic by removing the requirement of priestly assistance from the rituals. The result was a subtly transformed sort of magic that was in turn made available to a vernacular audience. At the same time, the fact that it was copied for a priest demonstrates that learned magic also continued to be the preserve of an educated and even clerical elite.

Scholars often give the impression that the Renaissance brought about a profound and widespread rewriting and revision of magic from the 1480s onward. This is a gross oversimplification, if not a genuine misrepresentation of the culture of magic in the sixteenth century in which medieval ritual magic was preserved and transmitted in its original form with tremendous enthusiasm. The great Renaissance writers, starting with Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, and followed later by Cornelius Agrippa and Giordano Bruno, produced striking and original new works on or involving magic that were profoundly influential in the development of Western esoteric traditions. However, the impact of these writers was sporadic and slow to take root, in significant measure because of the arcane nature of their works. In 1533 the Oxford necromancer Richard Jones expressed frustration with Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia, saying that it was “of very small effect.” Although this might be taken as the bravado of a middlebrow conjurer, the comment reflects the attitude of many sixteenth- century scribes of magic. Jones evidently regarded it as important and acquired a copy in the very year it was first published. But unlike the highly scripted ritual magic texts Jones was used to, Agrippa was more concerned to make larger arguments about the nature of magic and the cosmos and actually provided very little concrete information on what to do with all the materials he provided or how to do it. In fact, Agrippa’s project sought to reformulate magic in the original and proper form practiced by ancient Hebrew prophets and patriarchs. His whole point—which was very much the same among the other Renaissance writers—was that contemporary magic got it wrong and should be entirely reformulated. As a result, the works of the great Renaissance mages did not accord well with the needs, inclinations, and sensibilities of most practicing magicians, who saw no need to build a different system of practical magic from obscure sources in ancient Greek and Hebrew.

Predictably, most sixteenth- century scribes, even those who were educated enough to read Latin or other ancient languages, filled the pages of their books with the highly scripted works of medieval ritual magic. In fact, most important medieval ritual magic texts are known primarily through copies made in the sixteenth century by scribes eager to preserve these older traditions. Ironically, the printed works pseudonymously attributed to Agrippa and the other works bound with them were far more influential in sixteenth- century books of magic than his legitimate works because they reflect these earlier forms of scripted ritual magic. By contrast, Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia took up a role as the premier magic sourcebook or encyclopedia of magic, one that it has consistently played to the present day. From it scribes drew scattered elements that they inserted into magic that otherwise retained its old forms in most respects. In all this, other writers like Pico, Ficino, and Bruno, who were significantly less accessible than Agrippa, were all but irrelevant. As we shall see, the Latinate author of the Boxgrove Manual reflects this situation. He employed Agrippa both for nuggets of information and also for some framing cosmological concepts as he constructed a system based in significant measure on medieval ritual magic manuscripts and new printed works of practical magic, themselves based largely on medieval sources.

Although it contains some ritual magic material, another form of scripted magic fills most of the pages of the Antiphoner Notebook. Charms and protective amulets constituted what may be the most common genre of magic in the later Middle Ages. They were certainly the most ubiquitous, as charms may be found not only in medical works and dedicated collections, but scattered throughout the library in margins, flyleaves, and elsewhere. Unlike ritual magic, charms were practiced as part of a conventional regimen of healing and protection from misfortune by a much wider demographic including both clerical and lay, wealthy and poor, educated and illiterate. Also, unlike ritual magic with its complex liturgical rituals and cosmologies, charms are quite simple and short and based on the conservative bedrock of conventional and everyday religious practices. They employ basic prayers such as the Pater Noster and Ave Maria, formulae like the Credo, the invocation of saints, divine names, religious historiola, and gestures like the sign of the cross for healing and protection. As a kind of lay liturgy, these changed very little over time except in minor textual ways. Many charms have long textual histories spanning numerous centuries and were very broadly transmitted in Europe. Even the Reformation, which had been attacking the “superstition” of Catholic practices for decades by the time the Antiphoner Notebook was written, had little effect on the attractiveness of this aspect of the old religion. Many of the charms the scribe copied are almost identical to ones found in fourteenth- century manuscripts. A fuller discussion of this genre may be found in the introduction to that work below.

Although I have argued that magic texts changed as they were transmitted to vernacular and nonclerical contexts and that this process accelerated in the sixteenth century, I have on balance emphasized continuity with the past. The older traditions were preserved in their medieval forms, and when scribes copied magic texts they were overwhelmingly medieval in origin. Even if they were simplified the general outlines of the magic remained more or less consistent. To emphasize these forms of continuity through the sixteenth century in medieval ritual magic and charms, however, is only part of the picture. The sixteenth century brought with it a host of dramatic changes that had a direct impact on magic. By comparison, from the mid- thirteenth to the fifteenth century the broader intellectual and social conditions that informed the conception and practice of magic were relatively stable in England. Most importantly, theology and religious practice did not change in any significant way. The rise and persecution of the Lollards certainly inspired a more conservative attitude toward heresy, but the continental habit of associating heresy with magic and apostasy was never strong in England and, in any event, Lollards were not associated with magic. This being said, magic consistently was understood as a matter for Church rather than secular courts, except in highly unusual cases. Scholastic culture dominated the intellectual world without significant challenges, and the universities remained the center of intellectual life. If intellectual condemnations of magic became more sophisticated in their awareness of magic texts, the basic message of those condemnations did not change. Unsurprisingly, although the textual traditions were fluid and the manuscripts of magic often highly individual, the basic nature of magic remained fairly stable to the end of the fifteenth century, particularly in its close relationship with conventional religion. The same could not be said for the sixteenth century.

Excerpt ends here.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.