The Creation of the French Royal Mistress

From Agnès Sorel to Madame Du Barry

Tracy Adams and Christine Adams

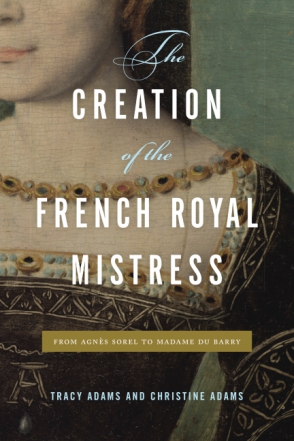

The Creation of the French Royal Mistress

From Agnès Sorel to Madame Du Barry

Tracy Adams and Christine Adams

“Provides us with a new way of understanding the role of the royal mistress as integral to the workings of the French Crown. Scholars, students, and general readers alike will find much to explore here.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Beginning in the fifteenth century, key structures converged to create a space at court for the royal mistress. The first was an idea of gender already in place: that while women were legally inferior to men, they were men’s equals in competence. Because of their legal subordinacy, queens were considered to be the safest regents for their husbands, and, subsequently, the royal mistress was the surest counterpoint to the royal favorite. Second, the Renaissance was a period during which people began to experience space as theatrical. This shift to a theatrical world opened up new ways of imagining political guile, which came to be positively associated with the royal mistress. Still, the role had to be activated by an intelligent, charismatic woman associated with a king who sought women as advisors. The fascinating particulars of each case are covered in the chapters of this book.

Thoroughly researched and compellingly narrated, this important study explains why the tradition of a politically powerful royal mistress materialized at the French court, but nowhere else in Europe. It will appeal to anyone interested in the history of the French monarchy, women and royalty, and gender studies.

“Provides us with a new way of understanding the role of the royal mistress as integral to the workings of the French Crown. Scholars, students, and general readers alike will find much to explore here.”

“With this excellent and seamlessly coauthored study, Christine and Tracy Adams delve into the creation of the post of the royal significant other—an often overlooked category of premodern female power and influence. They move beyond the salacious to an intellectual understanding of the complementarity of gendered premodern political power.”

“Intensively researched and engagingly written, this innovative work traces the history of the royal mistress in France, demonstrating her impressive social, political, and cultural influence. The book examines the development of this unique position, which was a counterpart (and rival) to that of the queen—ultimately arguing that Marie Antoinette fell by trying to play the traditional roles of both queen and mistress, rocking the foundations of French queenship and the court itself.”

“At last, a scholarly academic book on French royal mistresses, extensive in its coverage from Agnès Sorel to Du Barry, and one that can be used with confidence in teaching this subject in courses on women in power and the development of courtly politics in the early modern period. A comparative analytical discussion of the uses of ‘soft power’ by nonroyal women at the French court is long overdue.”

“The extraordinary position of the ‘official’ mistress (maîtresse en titre) of reigning kings of France—from Agnes Sorel in the fifteenth century to Mesdames de Pompadour and du Barry in the eighteenth—is Christine and Tracy Adams’s focus in this scholarly and illuminating study. They do full justice to the post’s colorful incumbents, who casually broke their age’s gender conventions, but also brilliantly highlight the persistent and multifaceted ways—sexual partner, political adviser, patronage hub, diplomatic back channel, cultural patron, ostentatious fashion adornment—in which these women served the monarchy.”

“This is a valuable contribution to our knowledge of the French monarchy and the changing roles and relationships of women at the royal court.”

“Based on an extensive bibliography, the authors assiduously synthesize and reevaluate the research on these royal mistresses to bring to light the ways in which they helped shape history.”

Tracy Adams is Professor of French in the School of Cultures, Languages and Linguistics at the University of Auckland. She is the author of three books, including Christine de Pizan and the Fight for France, also published by Penn State University Press.

Christine Adams is Professor of History at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. She is the author or coeditor of four books, including A Taste for Comfort and Status: A Bourgeois Family in Eighteenth-Century France, also published by Penn State University Press.

Acknowledgments

Introduction: What Was It About France?

1. The Beginning of a Tradition: Agnès Sorel

2. A Tradition Takes Hold: Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly

3. Diane de Poitiers: Epitome of the French Royal Mistress

4. Gabrielle d’Estrées: Never the Twain Shall Meet

5. The Mistresses of the Sun King: La Vallière, Montespan, Maintenon

6. Tearing the Veil: Pompadour and Du Barry

Epilogue: Mistress-Queen and the End of a Tradition: Marie Antoinette

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

What Was It About France?

Frederick the Great, discussing the ruinous propensity of German princelings to imitate Louis XIV in book 10 of his 1740 Antimachiavel, put the French royal mistress on a par with the Versailles court and the French army in the list of outrageously expensive items that the princelings coveted. “There is not a cadet of a cadet line,” he scoffed, “who does not imagine himself as a sort of Louis XIV: he builds his Versailles, he has his mistresses, he leads his army.” Christoph Wieland, writing three decades later, accords the royal mistress a similar role. The enthralling Alabanda, who keeps the eyes of King Azor averted from the misery of his people, can only be a comment on the extraordinary position of the French royal mistress in her setting of unimaginable opulence. What was evident to these German eyes remains so: whether one found the French royal mistress fabulous or appalling, she was a constituent element of the king’s grandeur. No one today would underestimate the importance of her splendor for bolstering the monarchy. But in addition to her visual role, she was a politician. True, not every royal mistress wielded clout. Contemporaries such as the Duke of Luynes distinguished between real and temporary holders of the role. Even if the rumor that Madame de Pompadour was installed at Versailles was true, “she was only a fling [passade], not a mistress,” Luynes asserted, incorrectly, as it happens. However, the most powerful mistresses rivaled the king’s closest advisers in terms of influence.

This study explores the sociogenesis and development of the position in France, examining the careers of nine of its most significant holders: Agnès Sorel, Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, Diane de Poitiers, Gabrielle d’Estrées, Françoise Louise de La Baume Le Blanc, Françoise Athénaïs de

Rochechouart de Mortemart, Françoise d’Aubign., Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, and Jeanne Bécu. Although kings had always had extraconjugal sexual partners—some of them powerful, such as Alice Perrers or Jane Shore—only in France did the royal mistress become a tradition, a quasi-institutionalized political position, generally accepted if always vaguely scandalous. And yet the position has been studied only in popular narrative histories intended to titillate. Other powerful female roles central to royal family life, such as the queen, the queen’s entourage, and the female regent, an unofficial role once considered somewhat illegitimate, have received serious attention in recent years, as have individual mistresses.6 However, the important and enduring position of French royal mistress per se has not been explored.

The study’s point of departure is a simple question: What was it about France? We would like to be very specific about our approach to this question. The creation of the role could be examined from any number of valid and enlightening perspectives. For example, it could be approached through a psychoanalytic lens, to hypothesize about the hidden emotional reasons why the role emerged when it did. Or it could be examined within the context of the Querelle des femmes, that long-term debate over the merits and faults of women, which corresponds, chronologically, to the appearance of the powerful royal mistress in France. However, given our own critical inclinations, we have opted to examine the intellectual, emotional, and physical environment that made emergence of the role possible.

We take as the basis of our analysis Fernand Braudel’s three-part schema of history, which differentiates long- from medium-term structures and both of these from short-term events, and, in this introduction, we initiate the study by applying the schema to the period between 1450 and 1540. AgnèsSorel, often considered to be the first significant French royal mistress, died in 1450; around 1540 Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, the Duchess of .tampes (1508–1580), begins to appear in ambassador reports as a central figure in court politics. As we will see in chapter 1, although indirect evidence attests to Agn.s’s political influence, it was not widely recognized during her own time. In contrast, no one doubted Anne de Pisseleu’s power. Between these two dates, then, something occurs that makes it possible for the king’s mistress to be taken seriously as a political adviser. We trace the convergence of structures and events in France during the period in question that allowed this to happen, first exploring a long-term structure that was a precondition for the position, a particular idea of gender already in place by the period that we are exploring. Conditio sine qua non for the royal mistress, this notion of gender also formed the basis for female regency, and, because this notion of gender is articulated in treatises on female regency, we start by examining how this slightly earlier and more familiar role was conceptualized. But if the same assumptions about gender support both roles, the royal mistress does not derive from the female regent. Rather, the royal mistress is a female version of the royal mignon, a medium-term structure originating in the mid-fifteenth century. Therefore we turn next to the mignons, or favorites, groups of young men associated directly with the king, who eventually admitted women among their number—although only one at a time. But under what circumstances was this role opened to women? To conclude our discussion of the convergence of structures that permitted the development of the royal mistress, we examine the position in the context of another long-term structure, the widely discussed theatricalization of the royal court under François I (b. 1494, r. 1515–47), which produced an environment within which women took part in “a vital system of communications through which messages [were] transmitted, channels opened up; they investigate[d] possibilities through talking to the right people, before men, by now confident of success, [made] more direct overtures.”

The role of powerful royal mistress became imaginable with the intersection of these structures. Still, it had to be activated by an intelligent and charismatic woman associated with a king willing to be advised by women. In other words, the position’s realization depended on what Braudel describes as particular events layered on top of the structures that we examine in this introduction. These events form the content of the following chapters in which we examine the individual careers.

A Particular Idea of Gender

Although queens had earlier served as regents, under Isabeau of Bavaria (1371–1435) and Anne of France (1461–1522) a genuine preference for female regents took hold. Ordinances promulgated by the mad king Charles VI (b.1368, r. 1380–1422) on behalf of Queen Isabeau reveal the logic behind this preference. Fearing that he would die prematurely after his earliest psychotic breakdowns in 1392 and 1393, the king settled what would happen in the case of his death, awarding regency of the realm (“government, guard and defense”) to his brother, Louis of Orléans (1372–1407), and guardianship of the young king to his queen, Isabeau, aided by his uncles. But Louis’s primacy led to rivalry with the royal uncles, each side accusing the other of wanting to usurp the throne. Hoping to lessen the possibility of civil war, Charles VI abolished regency altogether in an ordinance of 1403, stipulating instead that in the event of the king’s death, his heir would succeed immediately, whatever his age. Minus a regent, the queen mother, as guardian, would hold the reins of power, although her minor son “officially” ruled. The advantage of this scenario was that unlike a male regent—say, the minor king’s paternal uncle—the queen would prioritize not her own career but the welfare of her son. As Charles VI’s ordinance asserts, a mother “has a greater and more tender love for her children, and, with a soft and caring heart, she takes care of and nourishes them more lovingly than any other person, no matter how closely related.”

But maternal instinct was not the only basis for female preference. Here we need to consider the conception of gender underwriting the preference—that is, a long-established assumption that women were legally inferior to men but politically as capable as them. A number of conceptions of gender coexisted in late medieval and early modern France. However, this paradoxical one was particularly significant in shaping the experience of sexual difference among the nobility and therefore in supporting female regency. The conception undergirded feudal law, which allowed women to wield authority in the absence of a husband, son, or brother, but only under such circumstances.14 Political theoretician Christine de Pizan (1365–1431) gives the first self-conscious articulation of the principle, foregrounding the “natural” differences between men and women while insisting that women could perform as well as men in all things. As she recounts in her Livre de la mutacion de fortune of 1402, when her husband died she took over his role, metamorphosing into a man. True, women were excluded from certain positions by God’s viceroy Nature, Christine admits. Her father had hoped to pass his precious “stones” of astrological and medical knowledge on to a son. But Christine was a girl, resembling her father in all things: manner, body, and face. Only her “sexe” was different, and, for this reason, she could not inherit her father’s riches, although she could have done the job. Or, as a treatise on natural law of 1601 asserts, female modesty and the virtue particular to the sex, not any intellectual disadvantage, render reigning or commanding “souverainement” inappropriate for

women.

This idea that women were fit for all jobs but legally restricted from taking on certain ones except when there was no man to do it was common across Europe. What was unique about France, however, was the vision’s instantiation in the so-called Salic Law, which was elaborated over the course of the fifteenth century. True, the Salic Law excluded women from succession to the throne under any circumstances. But it implicitly allowed them to govern as regents. Indeed, by making them legally incompetent to succeed and therefore unable to usurp the throne, it created a tendency to favor them as regents. In this way, it gave a legal basis to the assumption that the queen mother was the safest choice for regent—set out in Charles VI’s regency ordinances—and further enhanced the advantage that she already enjoyed by virtue of her presumed maternal instinct. That the Salic Law was understood in this way is clear from seventeenth-century regency treatises. Pierre Dupuy (1582–1651) sets out what we might call the “safety” argument in his Traité des régences et des majorités des rois de France, first printed in 1655: “The principal reasons for this choice [of queen as regent] are based on . . . the natural affection of a mother for her children and [the fact] that there can be no suspicion of any danger for the princes committed to their care.” He then references the Salic Law, writing that “women, by virtue of their sex, are less capable of invading the State [Estat] of their children than any other person” for the reasons that “by the law of the State [Estat], they are excluded from the royalty; that it is impossible to imagine that it would even enter their minds to try to achieve such a thing; that they cannot be helped by anyone at all, not possessing this basic requirement; that they cannot act on their own, but [only] through others, in all the principal acts of their administration and particularly in acts of war and affairs of great resolve.”19 Robert Luyt in 1652 states the point still more forcefully: “Queens have normally been preferred in this choice to all Princes of the Blood and other lords, religious or secular, for the same reason, that we do not need to fear that they would usurp the crown, because they are precluded from doing so by the fundamental Law of this monarchy.”

The Salic Law, then, paradoxically created an opportunity for female authority. But it created a very particular conception of authority, forcing female regency to be imagined as a sort of open secret in which the king—a child—reigns, although it is in fact his mother who does the work. As Lucien B.ly observes, a very young prince such as Charles IX did not manage European affairs. In reality, the Guises and, especially, regent Catherine de M.dicis wrote the letters carried by French envoys, signed by the young monarch. And yet Dupuy’s treatise insists, as we saw above, that female regents could not act on their own. Scholarship on female regency such as Katherine Crawford’s Perilous Performances describes how the queen mother “performed” her maternity to cover her governing. We will return to this notion of the open secret.

Another aspect of the paradox is central to how female governance was imagined, although it is never explicitly stated in regency treatises. Although Christine de Pizan precedes the heyday of the Salic Law, she voices, as we have seen, the principle on which it was founded. We noted that for Christine a powerful woman was always a substitute, like Christine herself metamorphosing into a man. Equally important here, however, she also constructed female power as the necessary supplement to male power. In the Livre de la cité des dames of 1405, Christine describes gender differences as complementary. “God wanted men and women to serve him differently, and to help each other and give each other mutual aid, each according to his manner,” explains the allegorical character Reason, “and he thus created the two sexes to be of different natures, as necessary to the accomplishment of the tasks.” In her Livre des trois vertus, Christine explains that men are reactive because they are hot, whereas women are moist, cold, and peaceful, and therefore integral to maintaining order. When war threatens the kingdom, writes Christine, the princess is “the means of peace and harmony.” She works “to avoid war because of the trouble that can arise from it.” She explains to warring lords that “if they would like to make amends or make suitable reparations, she would happily make an effort to try to find a way to pacify her husband.” But Christine saves her clearest formulation of female power as the necessary supplement to the male version for her final known work, the Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc, which, proclaiming the recent victories of the French over the English, recalls that Charles VII (b. 1403, r. 1422–61) would not have prevailed had it not been for Joan of Arc: “And you Charles, King of France, seventh of that noble name, who have been involved in such a great war before things turned out at all well for you, now, thanks be to God, see your honour exalted by the Maid who has laid low your enemies beneath your standard.”25 Joan was required for Charles’s victory.

If the Salic Law was at times bolstered by misogynistic arguments, the principle of female exclusion was imaginable without recourse to such arguments, simply on legal grounds, common notions about maternal instinct and female modesty, and the traditional view of men and women as complementary, equally necessary, components of a whole (the absent or minor king could not rule without his mother). We return now to the official royal mistress, whose role was based on the same assumptions about gender. As Françoise Autrand has noted with reference to the fifteenth century, “In the western Christian model, power has a feminine side (‘face’).”26 True, for most great lords, this feminine aspect of their authority was represented by their wives. The queen of France undoubtedly played a crucial role in the configuration of royal power, representing mercy in the eyes of the public. However, with few exceptions, she was foreign, inevitably raising suspicions of prior loyalty and, among courtiers, the need for another, more secure way to access the king. In contrast with the queen, the royal mistress was always French and utterly devoted to the king.

Excerpt ends here.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.