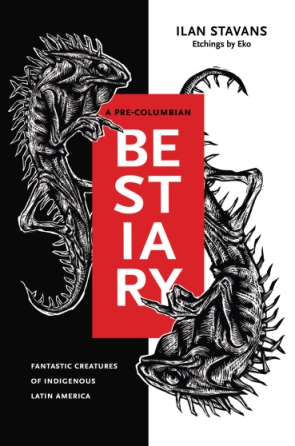

A Pre-Columbian Bestiary

Fantastic Creatures of Indigenous Latin America

Ilan Stavans with etchings by Eko

A Pre-Columbian Bestiary

Fantastic Creatures of Indigenous Latin America

Ilan Stavans with etchings by Eko

“The imaginary and real beings described by Ilan Stavans with whimsy, wit, irony, and, most of all, wonder, emerge from the pre-Columbian and colonial Americas to remind us that even in our own decolonial times, the imaginary and the nonimaginary, the fantastic and the historical, the speculative and the real continue to coincide in the Americas on the elusive line between fact and fiction, where ‘what is known and what is hoped for intermingle.’”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

From the siren-like Acuecuéyotl and the water animal Chaac to the class-conscious Oc and the god of light and darkness Xólotl, the magnificent entities in this volume belong to the same family of real and invented creatures imagined by Dante, Franz Kafka, C. S. Lewis, Jorge Luis Borges, Umberto Eco, and J. K. Rowling. They are mined from indigenous religious texts, like the

Popol Vuh, and from chronicles, both real and fictional, of the Spanish conquest by Diego Durán, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, and Fernando de Zarzamora, among others. In this playful compilation, Stavans distills imagery from the work of magic realist masters such as Juan Rulfo and Gabriel García Márquez; from songs of protest in Mexico, Guatemala, and Peru; and from aboriginal beasts in Jewish, Muslim, European, British, and other traditions. In the spirit of imaginative invention, even the bibliography is a mixture of authentic and concocted material.An inspiring record of resistance and memory from a civilization whose superb pantheon of myths never ceases to amaze,

A Pre-Columbian Bestiary will delight anyone interested in the history and culture of Latin America.“The imaginary and real beings described by Ilan Stavans with whimsy, wit, irony, and, most of all, wonder, emerge from the pre-Columbian and colonial Americas to remind us that even in our own decolonial times, the imaginary and the nonimaginary, the fantastic and the historical, the speculative and the real continue to coincide in the Americas on the elusive line between fact and fiction, where ‘what is known and what is hoped for intermingle.’”

“This is a delightful book. It is a parade, in the arbitrary order of importance that the alphabet allows, of creatures throughout indigenous America, from Aztlan southward, and that show up in the range of books that Stavans references. Challenged to pronounce their names and to imagine their shapes and attributes, the reader will recognize how uncanny the continent is, both strange and familiar.”

“This alphabetic delight offers not only a brief anthology of pre-Hispanic imaginary beings but also a door to the secret links between collective imageries that appear to be distant in space and time—although they all live in people’s dreams, just like those Freudian insects called Colotls. Bestiaries have their own literary tradition in the Latin American lands (both before and after colonization), ranging from the Mayas, Incas, or Aztecs to contemporary masters such as Borges, Arreola, or Wilcock, which is one of the multiple reasons why the volume is so arresting. Ilan Stavans manages to turn deeply erudite research into personal introspection (including his own father under the form of a Nahuatl grasshopper), and vice versa, making it ‘a double bird,’ just like the Aztec flying Zulin ‘that exists by looking at the mirror.’ Only one fantastic creature seems to be omitted here: this very exquisite book.”

“An inspiring record of memory from a civilisation whose pantheon of myths is captivating, A Pre-Columbian Bestiary will delight anyone interested in the history and culture of South America.”

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, publisher of Restless Books, and host of NPR’s podcast In Contrast. He is the recipient of numerous international awards and honors, and his books have been translated into twenty languages. Among his recently published books are two Penn State University Press titles: the graphic novel adaptation of Don Quixote of La Mancha, illustrated by Roberto Weil, and The Return of Carvajal: A Mystery, illustrated by artist and illustrator Eko, whose engravings are also featured in this book.

Preface

Acuecuéyotl

Amaru

Azcatl

Camazot Tzootz

Chaac

Chachalaca

Chapulín

Chicchán

Chuen

Colotl

Coyametl

Cuetzpalin

Dzaby

Ehecatl

Hixx

Huexólotl

Huitzin

Iguana

Imix Cipactli

Itzpapalotl

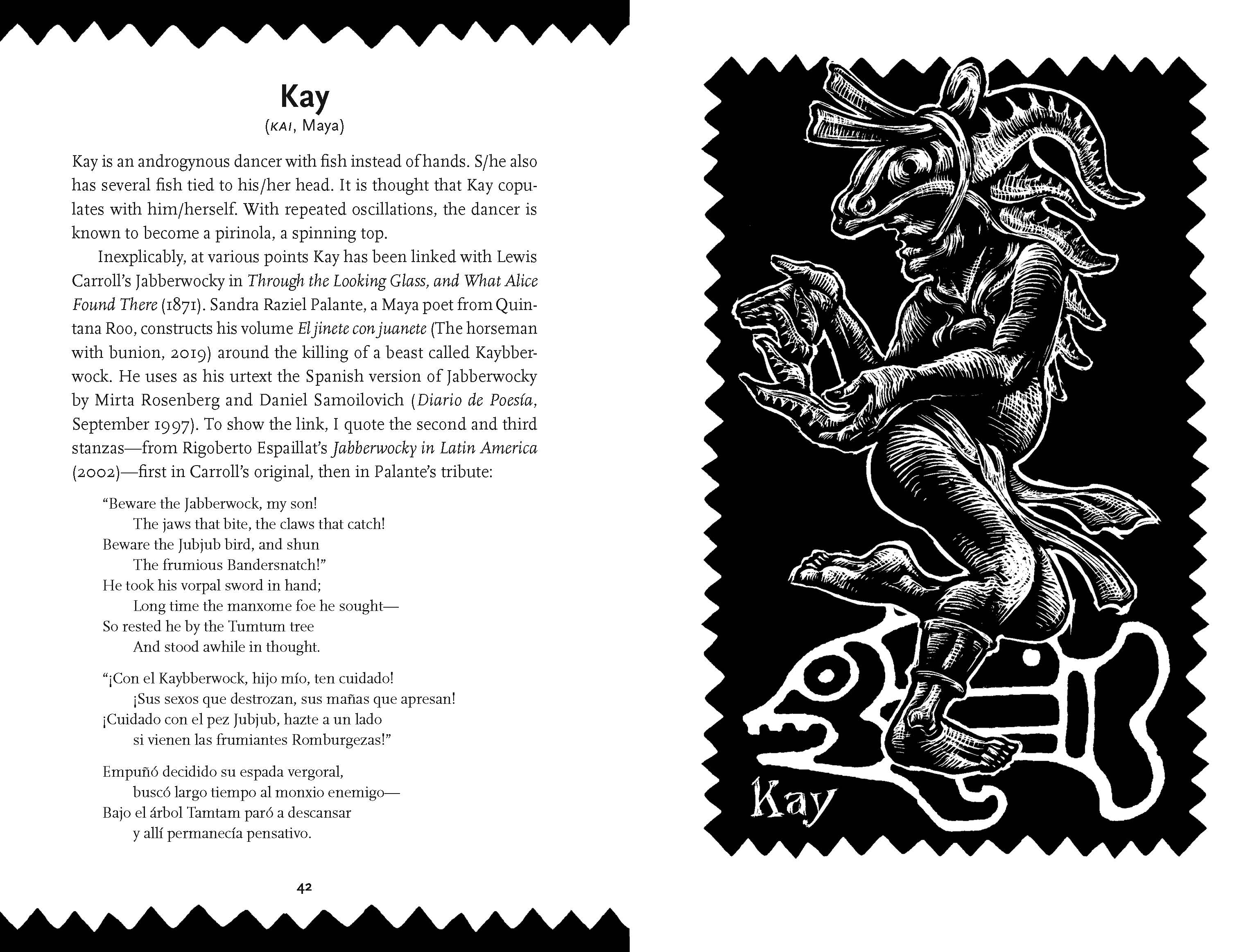

Kay

Kuntur

Lama Glama

Lama Guanacoe

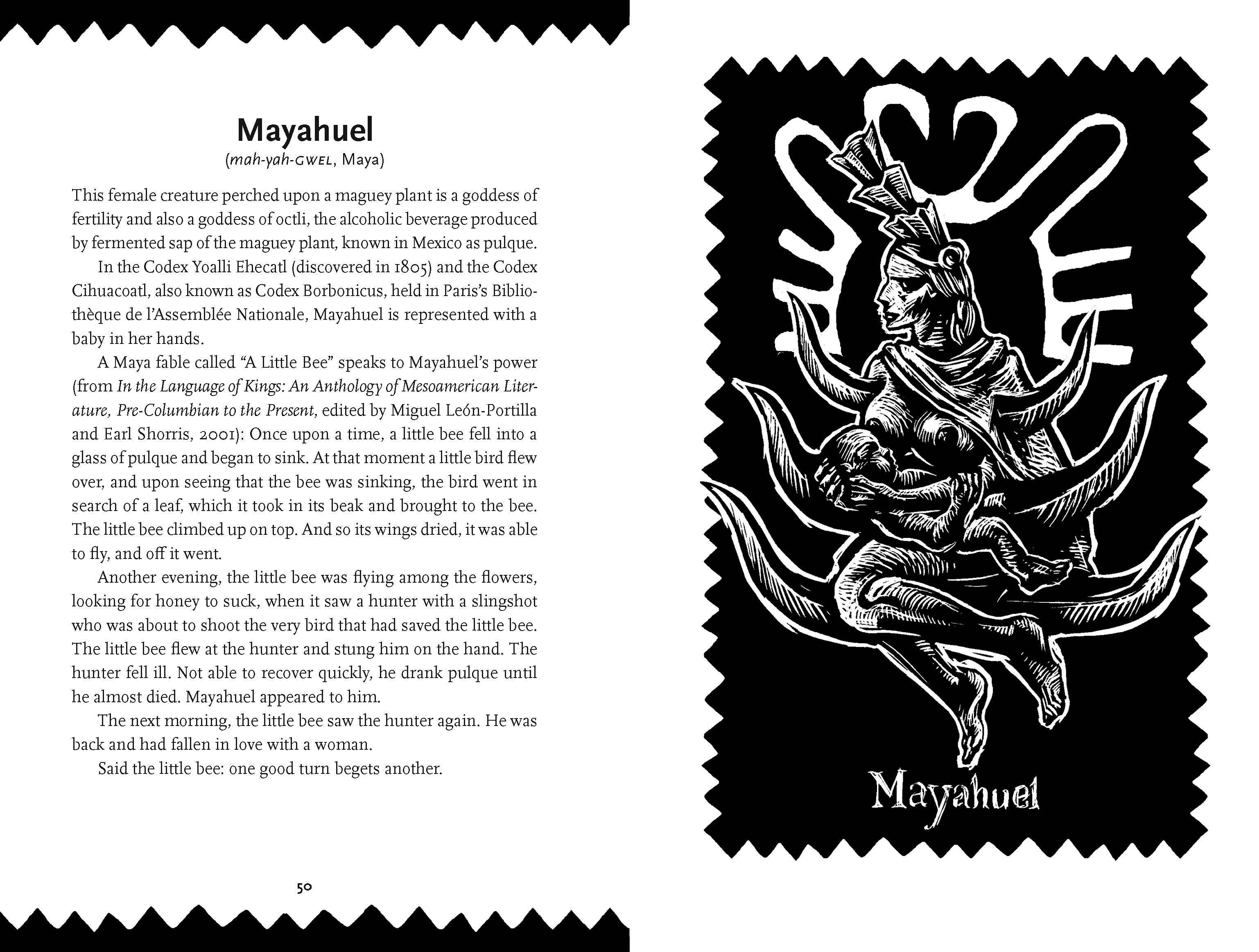

Mayahuel

Michin

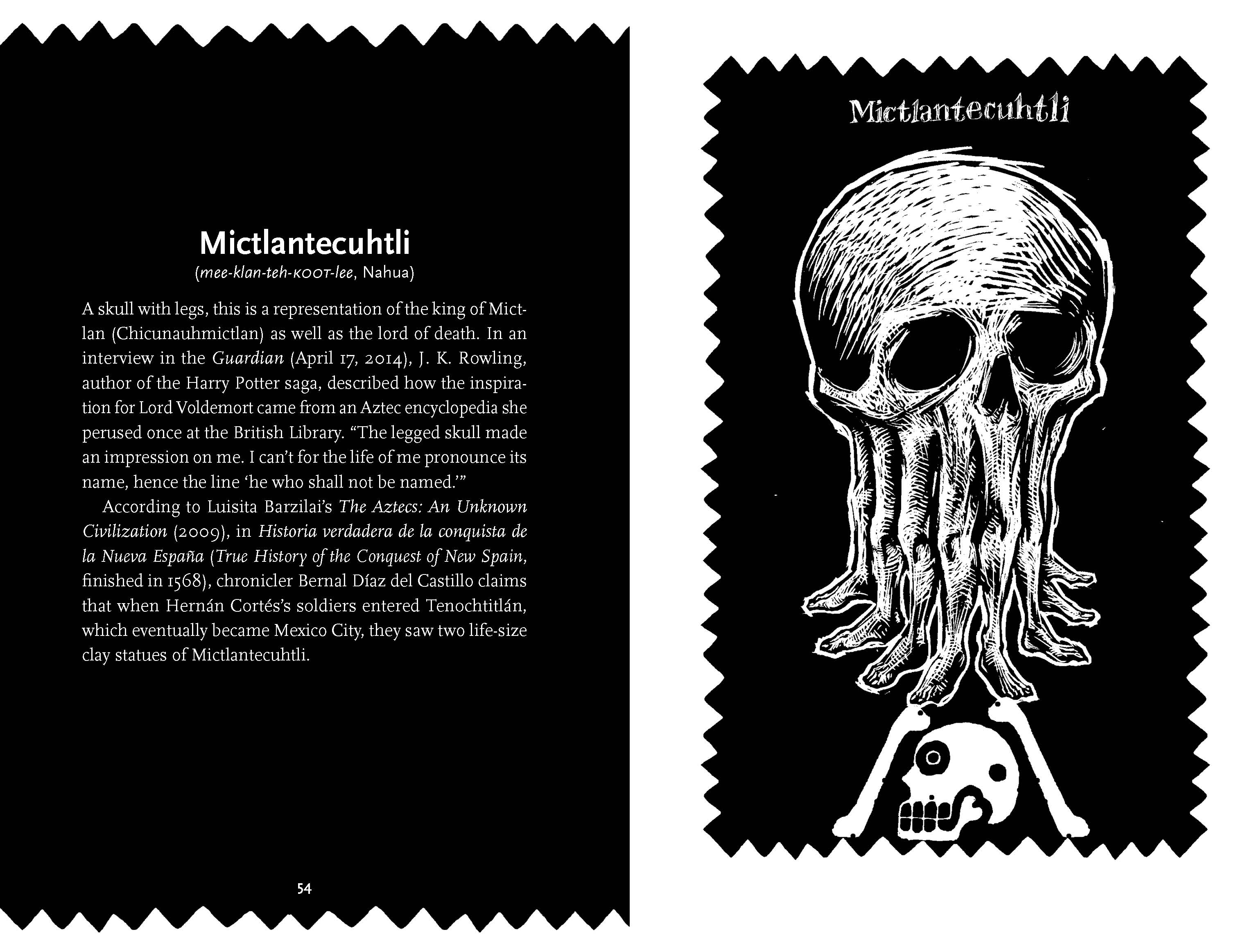

Mictlantecuhtli

Montizon Puskat

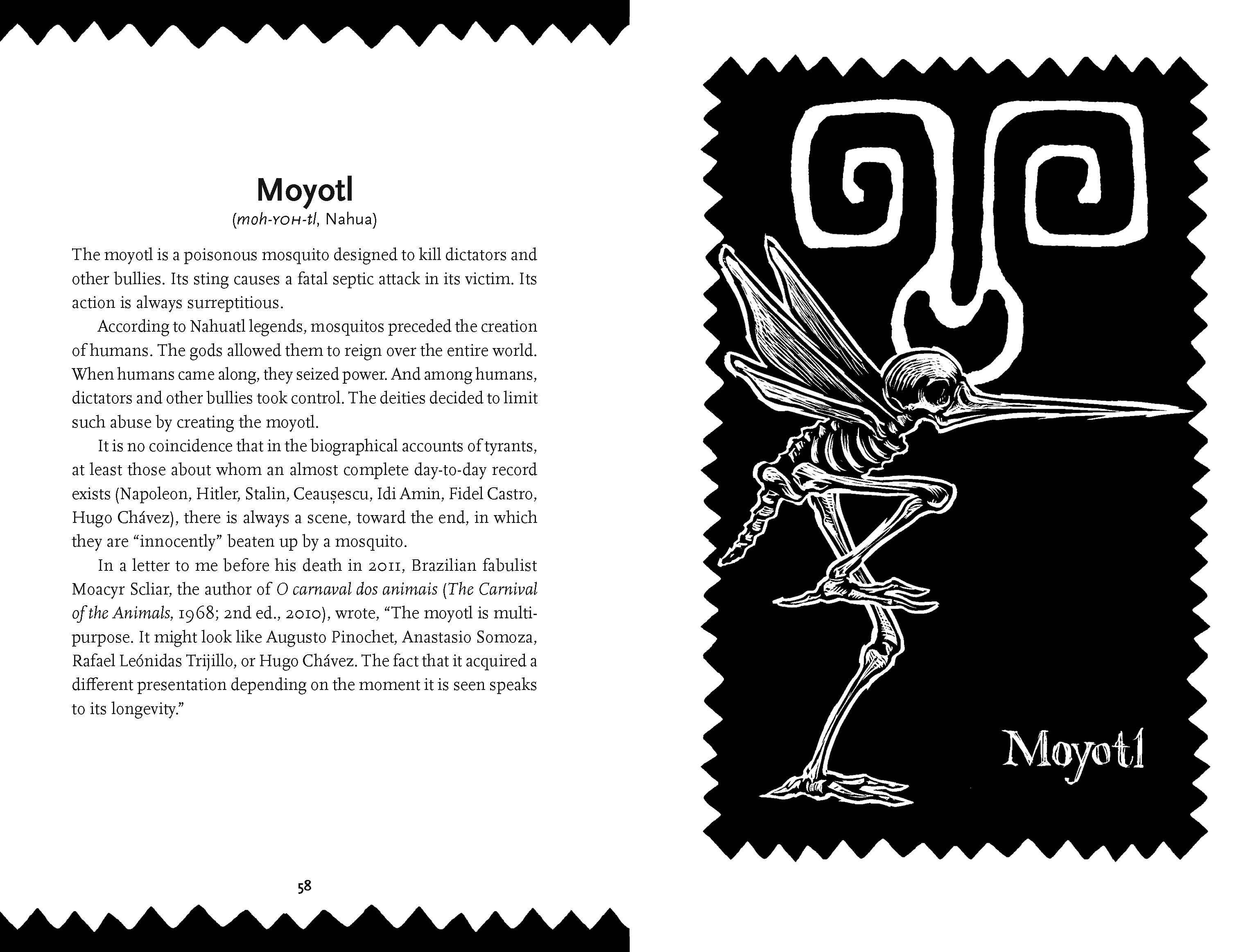

Moyotl

Nahual

Oc

Ocelotl

Omecihuatl

Pauahtun

Tepeyólotl

Thiuime

Tlalcíhuatl Toad

Tochtli

Toci

Tonatiuh

Uturunku

Utzimengari

Xiuhtilán

Xólotl

Xtabay

Zulin

Further Readings

Index

Preface

A few years ago, during a shamanic ceremony in Colombia, I ingested ayahuasca, made of Banisteriopsis caapi, a South American liana employed for hallucinogenic purposes. Ayahuasca is a “plant teacher.” It pushes the mind into unforeseen realms. No wonder indigenous tribes in the Amazon make it an essential companion for religious quests.

Using words to describe what I went through defeats the experience. I wrestled with this challenge in the book The Oven (2018), which also became a one-man theater show staged across the United States. The extraordinary out-of-body education I had left a deep mark on me. I felt unconfined, physically as well as spiritually. At one point, I miraculously underwent a mutation that turned me into a jaguar roaming for prey in a vast landscape.

Once I got home, I immediately reread the Popol Vuh (1554–58), the sacred origin book of the Maya. I became fascinated by the multiple adventures of Hunahpu and Ixb’alanke, twins who at one point traverse the underworld, known as Xibalba—a habitat as intricate as Dante’s hell—where they face, among dozens of other creatures, camazotz, bat monsters. In the narrative, these creatures have the terrifying strength of the Cyclops in Homer’s The Odyssey.

I soon realized that in the shamanic ceremony I had also visualized myself into an assortment of other creatures, a few of them impossible to describe: part human, part-deity, with a few recognizable features but many more I had never encountered before. I delved into pre-Columbian sources—encyclopedias, testimonies of the Spanish conquest, historical chronicles of life in colonial times under European rule—in search of them. What I found astonished me: the sources I looked at were themselves rather inconsistent and described these beasts in fanciful fashion.

It took me time to understand: this ethereal quality is precisely what makes these creatures distinct. I felt the inescapable urge to retell Popol Vuh for a contemporary readership; I also got the inspiration that led me to compile this anthology of pre-Hispanic imaginary beings, quoting from both real and fabricated sources. In the land of Magical Realism, what better way to pay tribute to these creatures than to celebrate their insubstantial status? (Julio Cortázar, in La vuelta al día en ochenta mundos [Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, 1967], writes: “I have always known that the big surprises await us where we have learned to be surprised by nothing, that is, where we are not shocked by ruptures in the order.”) After all, I grew up in Mexico; I know how elusive the line between fact and fiction is. Latin America is where what is known and what is hoped for intermingle.

Needless to say, fantastic animals have always been present companions in human civilization. The Bible is full of them, not only unicorns and cockatrices (in the King James Version, 1611), angels and cherubim, but also Behemoth and Leviathan, aside, obviously, from the Almighty, an omniscient being with anthropomorphic qualities whose only limitation appears to be—surprisingly—not to have been able to clone itself.

The Greeks had sirens, centaurs, satyrs, chimeras, basilisks, phoenixes, Pegasus, Medusa, Cerberus, and other entities. The Middle Ages were a fertile era for the creation of these creatures too: golems, dragons, and griffins, among others, would all be considered cryptids today.

Modernity added its own contributions, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1823), Count Dracula, and the massive black earthworm known as Mihoc.o. The production of fantastic creatures has only intensified over the last century, especially in the English-speaking world, with J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–56), and, more recently, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter saga (1997–2007).

Of course, what is fantastic to one culture is mundane to another. I ask myself, What did the indigenous people of Hispaniola, the first Caribbean island on which Columbus set foot, think of the Italian explorer and his companions? They probably believed the visitors were either demons or gods. As the Talmud (Tractate Berakhot ) argues, we don’t see the world as it is; instead, we see it as we are.

The Americas have long been a popular location to find monstrosities. Scientists like Charles Darwin and Alexander von Humboldt and writers like Andre Breton, D. H. Lawrence, Allen Ginsberg all presented these continents as puzzling, deceptive places. This isn’t surprising; even today, the so-called New World remains a testing ground in which Europe envisions all sorts of enigmatic occurrences.

Jorge Luis Borges, along with Margarita Guerrero, edited the anthology Manual de zoología fantástica (Manual of fantastic zoology, 1957), expanded in 1967 and again in 1969 under a different title: El libro de los seres imaginarios (The Book of Imaginary Beings). It includes creatures like the pygmies mentioned by Aristotle and Pliny; the chimera, a three-headed beast with the head of a goat sprouting from its back, a lion’s head at its front, and a snake’s head on its tail; and Emanuel Swedenborg’s angels, “the perfect souls of the blessed and wise, living in a Heaven of ideal things.”

Perhaps most vividly, in Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967), a series of bizarre creatures visit the town of Macondo, including the gypsy Melquíades, who dies dozens of times yet is always youthful, and the naive and angelic Remedios la Bella, whose out-of-this-world beauty ultimately makes her fly into the sky—neither of which is portrayed as monstrous.

In truth, my interest in pre-Columbian creatures dates back further than my ayahuasca experience, to the late twentieth century, when I first read Moacyr Scliar’s O carnaval dos animais (The Carnival

of the Animals, 1968), which is full of the most whimsical American fauna. In my personal library, I have an array of volumes that attempt to portray them, a few of them lavishly illustrated. I have acquired artesanías that are the equivalent of action figures. I have talked, sometimes at length, about this obsession of mine with scholars and writers like César Aira, Frederick Luis Aldama, Diana de Armas Wilson, José Donoso, Ariel Dorfman, Carlos Fuentes, Moshe Idel, José Emilio Pacheco, Ricardo Piglia, Miguel León-Portilla, Moacyr Scliar, Earl Shorris, Doris Sommer, and Juan Villoro.

The current selection of forty-six beings emphasizes gods and beasts from the Aymara, Aztecs, Inca, Maya, Nahua, and Tabascos. It is limited to American creatures, both existent and invented, from texts dating back to the sixteenth century, although some came to be—and were certainly recorded in historical documents—after the Conquest and during the colonial period that stretched until 1810. Regardless of their textual traces, these beings are grounded in oral tradition, recorded in the works of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Diego Durán, and other missionaries and later expanded upon by mythmakers such as Ni.o Benítez, Carlos Castaneda, Óscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari (aka Xul Solar), and Guillermo del Toro. I’m deliberately loose with my primary source quotations and references, to the point of irreverence, distortion, and outright invention.

In my childhood and in travels during my adult years, I have personally seen a handful of these creatures with my own eyes. During a night of conversation, I described them in detail to the legendary Mexican artist Eko. His superb depictions are approximations based on indigenous codices.

Each entry begins with the creature’s name, a guide to its pronunciation, and the culture from which it comes. The “Further Readings” section at the end of this book invites the reader to peruse authentic and fictional sources.

In spelling names, I have chosen to approximate, though not always endorse, the rules established by Bolivia’s Instituto Iberoamericano de Lenguas Indígenas, Guatemala’s Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas, and Peru’s Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua.

My wholehearted gratitude to Patrick Alexander for his long-standing support, and to Alex Vose and Alex Ramos for their superb editorial work—three nonimaginary Alexes in a volume where coincidences reign.

—Ilan Stavans

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.