Gorgeous Beasts

Animal Bodies in Historical Perspective

Edited by Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist

Gorgeous Beasts

Animal Bodies in Historical Perspective

Edited by Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist

“This innovative, accessible, and thorough collection addresses an admirable range of historical and geographical contexts to demonstrate that the human relationship with other species is complex and overdetermined, and that human systems of knowledge and representation are crucial for negotiating this uneven terrain. An essential teaching text, Gorgeous Beasts will find a welcome home in the HAS classrooms of many disciplines.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

This collection presents the work of a wide range of scholars, critics, and thinkers from diverse disciplines: philosophy, literature, history, geography, economics, art history, cultural studies, and the visual arts. By approaching animals from such different perspectives, these essays broaden the scope of animal studies to include specialists and nonspecialists alike, inviting readers from all backgrounds to consider the place of animals in history and art. Combining provocative critical insights with arresting visual imagery, Gorgeous Beasts advances a challenging new appreciation of animals as co-inhabitants and co-creators of culture.

Aside from the editors, the contributors are Dean Bavington, Ron Broglio, Mark Dion, Erica Fudge, Cecilia Novero, Harriet Ritvo, Nigel Rothfels, Sajay Samuel, and Pierre Serna.

“This innovative, accessible, and thorough collection addresses an admirable range of historical and geographical contexts to demonstrate that the human relationship with other species is complex and overdetermined, and that human systems of knowledge and representation are crucial for negotiating this uneven terrain. An essential teaching text, Gorgeous Beasts will find a welcome home in the HAS classrooms of many disciplines.”

“With a multidisciplinary approach combining historical studies and the study of visual representations, with a period focus centered on the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but also reaching back to the Renaissance and forward to contemporary works, and with contributions from some of the most prominent and thought-provoking scholars in the field of animal studies, Gorgeous Beasts energetically advances the current conversation about the human uses of nonhuman animals. Several essays investigate and seek to remedy the lack of representation involved in past and present silences concerning the slaughter of animals, while others investigate the problematic representations of animals as creatures of the wild, objects of scientific study, trophies, or biomass to be harvested. The attention paid to the contemporary artists Daniel Spoerri and Mark Dion makes explicit the links between the historical analyses and our current situation. Raising provocative and important questions, this volume sets the terms for future studies of the representation of other animals by humans.”

“This book introduces us to gorgeous beasts—creatures we yearn for, treasure, misunderstand, and mistreat. Enclosure-endangered Atlantic codfish, bloodhounds unleashed on the Maroon uprisings in Jamaica, taxidermied elephants that conferred secondhand majesty on trophy hunters, slither-painting snakes, even dog-skin gloves and civet-scented perfumes (those animal-made objects): all testify to our human co-construction of, with, and by animals. In the book’s lush illustrations, the visual representation of animals has equal footing with their material and economic histories, and the result is a thought-provoking and sense-igniting treat.”

“Gorgeous Beasts is a gorgeous book. As the essays revel in the physicality of animal bodies in order to reveal why and how animals matter in history and art, so the volume celebrates the physical book. Extensively illustrated, expertly designed, and printed on sumptuous paper, it embodies the best of the exhibition catalogue and the scholarly text. Like a finely curated art exhibit, it speaks to the myriad and contradictory ways that animals matter through individual works that are a pleasure to behold, read, and contemplate.”

“Edited by Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist, Gorgeous Beasts brings together nine essays by some of the most sophisticated voices within animal studies to explore the histories and desires shaping human encounters with other animals, both alive and dead. . . . Gorgeous Beasts asks all the right questions. Its animal bodies are provocative, unpredictable, and potent. Meticulously researched and eloquently argued with clear, accessible language, the essays incite a knowing that grows beyond the page and into our daily lives with other animals.”

“The essays in this book explore the important, sometimes ambiguous roles that animals play in human culture.”

Joan B. Landes is Walter L. and Helen Ferree Professor of Early Modern History and Women’s Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.

Paula Young Lee is an independent scholar and the editor of Meat, Modernity, and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse (2008).

Paul Youngquist is Professor of English at the University of Colorado.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist

1 Animal Subjects: Between Nature and Invention in Buffon’s Natural History Illustrations

Joan B. Landes

2 Renaissance Animal Things

Erica Fudge

3 The Cujo Effect

Paul Youngquist

4 On Vulnerability: Studies from Life That Ought Not to Be Copied

Ron Broglio

5 The Rights of Man and the Rights of Animality at the End of the Eighteenth Century

Pierre Serna

Translated by Vito Caiati and Joan B. Landes

6 Calling the Wild

Harriet Ritvo

7 Trophies and Taxidermy

Nigel Rothfels

8 Fishing for Biomass

Sajay Samuel and Dean Bavington

9 Daniel Spoerri’s Carnival of Animals

Cecilia Novero

A Conversation with the Artist Mark Dion

Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist

Bibliography

About the Contributors

Index

Introduction

Joan B. Landes, Paula Young Lee, and Paul Youngquist

Lately there have been foxes. Outside the office window appeared the agouti shape of a lithe interloper. She basked in the winter sun, half-asleep on a stone seat in an adjacent amphitheater, comfortable and incongruous. Later, in London, the wind a hard slap to the face, she appeared again: fluffed and taut, her eyes flashing as she slid through shadows around trash bags, into the dusk. Who is this furred phantasm with her wily flesh?

To encounter an animal, especially unexpectedly, is to wonder, “what is this beast doing here?” It’s a question for which there are surprisingly few answers. Perhaps this fox is simply living, persisting in her vitality, doing her thing. Why she should do it between a Cineplex and a tube stop is perplexing, but there you have it. She persists, welcome or not. This fox comes to trouble comfortable assumptions about human privilege and animal obeisance. She lives beyond these distinctions, much like the fox captured in photographer Amy Stein’s image Passage in her Domesticated series (fig. I.1). Seated motionless atop the gravel-graded opening of a drainpipe, seemingly suspended between nature and culture, she evokes our paradoxical relationship to the “wild”: our desire to be part of nature while simultaneously taming it.

Gorgeous Beasts: Animal Bodies in Historical Perspective names a desire as much as a discovery. Animals realize a life that exceeds the small circle of our so-called humanity, a full and feral life irreducible to reason and its pale twin, propriety. While incessantly alluring to humans, indeed necessary to human existence, the proximity of animals to humans is a source of both their suffering and our delight. The title foregrounds the doubleness of human relations to animals, that is, the contradictory connections between human and nonhuman animals in different social contexts and places, ranging from early modern to contemporary times. The essays in this collection find animals abundant and audacious: horrific, fierce, tender, or vulnerable. Animals occasion new emotions. They attract and repel. They seduce, while too often becoming objects of unacknowledged violence. They dismantle old beliefs and also challenge humans to devise new ways of living in concert with and among easily overlooked or undervalued species. The book’s contributors address various ways in which humans and animals are linked within specific sociopolitical and intellectual contexts, including aristocratic and capitalist class structures, colonial trade and racial domination, liberal theories of rights and modern science. They call attention to the paradoxical ways in which animals have been assigned to the categories “wild” or “natural” and have been consumed and appropriated for different human purposes. These essays also reveal that animal-human relations are shaped by animals’ responses to, sympathy for, and interest in their human partners. Gorgeous Beasts draws generously upon visual as well as textual sources, integrating artistic with analytical, scientific, or literary responses to animal bodies, and showing how vision and curiosity play a significant role in human responses to animal beauty.

Picture a fox. In a simple sense, this is an act of imagination. A fox, or an image of one, appears in your head, and it represents real-life foxes. The image “fox” (whiskers, teeth, tawny fur, and bushy tail) stands in for the elusive, real, and absent thing. So an imagined picture of a fox is like a fox, only less so—the next-best thing to having one of your own, better, maybe, since foxes are not easy to domesticate. An imagined fox is cute, docile, clean: fox lite.

This is where things get tricky. Foxes may be hard to domesticate, but they come home in pictures. Representations domesticate them, turn them from living beings into signs of life. An image of a fox is a kind of compromise between its life and ours, a mingling of traces that produces a hybrid: neither quite fox nor quite human but something in between. This hybrid is a sign. It bears a resemblance to a fox. But it shows too the active touch of the imagination that produced it. One might ask of any given image of a fox, which fox does it signify? All foxes? Just a few? One particular fox in a Soho dumpster or a photograph by Amy Stein?

The work of the artist Mark Dion helps one see how much is involved in seeing animals. His installations and assemblages show how encounters with them take place on many registers at once. Animals are never just there to be seen, felt, or known. History situates them. Culture appropriates them (fig. I.2). Science defines them in one way, affection in another. Dion’s work reveals how much work it takes to see a fox, how much baggage one brings to any encounter with animal bodies. An installation titled The Delirium of Alfred Russel Wallace, originally staged in Vienna in 1994, illustrates the point with intelligence and wit (fig. I.3). At its center is a fox, stuffed and lying on its back in a hammock (color plate 7). Shrouded in mosquito netting, the hammock hangs between two trees, one living and one dead. Flanking each is an old steamer trunk surrounded by the tools of the naturalist’s trade: butterfly nets, specimen boxes, binoculars, maps, books, a shotgun, a bottle, and more. The scene resembles the campsite in Malaysia of the great explorer, naturalist, and co-discoverer of evolution, Alfred Russel Wallace, with one key difference: Wallace is the fox. An audible recording of Wallace reflecting on his life in the field completes the identification. Dion forces his viewer to question human encounters with animal bodies by substituting an animal body for that of a historically particular human.

<comp: insert figs. I.2 & I.3 about here>

To see the body of a fox here involves perceiving it in human terms. A panoply of discourses, technologies, and customs make it visible. Natural history frames the whole encounter, which is to say that “nature” is a historical invention. The scientific bias of that invention appears in all the gear for measuring and recording its details. But other kinds of tools are involved, too: a pot for cooking, a bottle for drinking, a lantern for driving back the dark. The animal body at the center of Dion’s installation appears as the object not so much of science as of the various histories and habits that sustain science as a form of knowledge. History unfurls a British imperialist backdrop to the great naturalist reposing in Malaysia. Culture packs the scene with European accoutrements. That fox in the hammock is the creature of a whole arsenal of tools and beliefs.

To encounter this fox is to acquire an awareness of the complex historical and cultural heritage that enables perception. Dion’s soundtrack doubles that awareness, as Wallace confesses his own inescapable bias: “I will often set foot on a land which no European eye has beheld, or see animals unknown to our world, or be treated to customs completely alien in origin; yet none of it stands in the foreground of my mind. My thoughts may be occupied by visions of the English countryside, or filled with fragments of an absurd and detestable children’s song, running a course in my head. London Bridge is falling down.” Such is the delirium of this naturalist in the field: part exotic sensation, part national identity, part foolish memory—and part fox. The spectacles resting on its black snout bring its stuffed body into focus as a complex object, composed as much of taxonomy, dream, and desire as of fur and flesh. Dion’s crowning irony is the impossibility of the perception his installation nevertheless documents. As the father of bio-geography and the author of Geographical Distribution of Animals, Wallace knew what his scientific treatise established: in Malaysia there are no foxes. Yet there one sleeps, conjured by science, culture, and delirium. The animal bodies encountered in Gorgeous Beasts share these contingent origins.

Marks of the Beast

Encountering animals turns out to be a much more complicated process than it looks. Representing them in signs requires a lot of stage setting before one can say with assurance, “oh, that fox,” “oh, that cat.” For the sake of simplicity, let’s say it involves at least two registers of perception, one erotic and the other historical. An old adage is worth pondering: people see what they want to see. Seeing involves desire. The (misogynist) popular history of the word “fox” makes the point obvious. Images, words, signs get tinged by the desire that invokes them. To focus perception on this particular object rather than that is to mark it as wanted. Seeing animals means marking them, making and remaking them in the image of desire. The other register of perception is historical. Any given image comes trailing a long history of representations that enables us to identify it with a fox or a cat. One important implication of this observation is that seeing is an act of history. Seeing animals means seeing them through a long, complex, invisible history of representations that name them, locate them, and value them, making it possible to exclaim, “that’s a fox!”

Animals inhabit environments altered by contact with human societies, just as human relationships are mediated by animals co-present in their various locales. Consider another familiar (domesticated) beast, the horse: an animal that has cohabitated with humans for millennia, playing a prominent role in human society. In agriculture, horses pulled plows, provided fertilizer and even food—as any visitor to a French boucherie chevaline, specializing in horse meat, can attest. Horses facilitated long-distance trade and played a decisive role in military conquest. Their hides provided leather to human populations. Given that we commonly think of horses as part of either a natural or a rural landscape, the horse’s role in modern urban life and industry can come as a surprise. The authors of The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century present the nineteenth-century city as the climax of human exploitation of horse power, crediting the horse with helping to build that age’s giant, wealth-generating metropoles. Yet this is not a simple story of animal as object or victim, human as exploiter. Surprisingly, horses also benefited from the new human ecology: “Their populations boomed, and the urban horse, although probably working harder than his rural counterpart, was undoubtedly better fed, better housed, and protected from cruelty. To the extent that it can be determined, the urban horse was also larger and longer lived than were farm animals. Thus the relationship was symbiotic—horses could not have survived as a species without human intervention, and dense human populations frequently relied on horses. . . . The European horse survived because it found an ecological niche as a partner for humans. In a sense this was co-evolution, not domination.” Co-survivor, co-evolver, and (no matter how lopsided) companion animal: the horse’s integration into the story of the nineteenth century’s emergent metropolis demands a more complex account than everyday assumptions allow, particularly when those assumptions require us to draw lines between what is domestic and what is wild, what is cultural and what is natural.

Amy Stein’s Domesticated series brings these issues into focus. In an image titled New Homes, two bobcats range unexpectedly into human territory (fig. I.4). One sits on a poured concrete foundation, sheltered by a skeleton frame made of wood. Another sits atop a wrapped package of lumber lying next to a pile of exposed planks. Predators at rest, these bobcats are seductive diplomats of danger, night watchers in daylight waiting for prey: rabbits hiding in tall weeds. Arrestingly lucid, the photograph resembles the kind of “Otherwhere” images published in National Geographic, which often highlight quixotic creatures wandering on the socioeconomic margins. The photographer is skilled. The viewer may feel admiration for the quicksilver reflex of the shutterbug’s eye. There seem to be luck, patience, and a story here, an allegory regarding the largesse of carnivores. The apparent poetry of the scene suggests abandonment, as if humans have departed forever, letting other predators take their place in nature’s hierarchy.

The story is all too familiar. The everyday experience of animals comes filtered through these sorts of waiting-room images. The brilliance of Stein’s photograph blooms in its familiarity, much like the famous bunch of grapes painted so skillfully by Zeuxis that birds tried to peck at them. According to the Roman historian Pliny, Zeuxis turned to his rival, Parrhasius, and asked him to reveal his own masterpiece. “Pull back the curtain!” Parrhasius ordered. Certain of his superiority, Zeuxis reached forward. Only then did he realize that there was nothing to pull back: the curtain was a painted image! Conceding defeat, Zeuxis muttered that his own work had fooled animals, but his rival had fooled another artist. Stein’s photograph adds the latest wrinkle to this famous challenge. This isn’t a lucky snapshot in the genre of travel photography but a staged tableau that exposes norms informing animal-human relationships. We are Zeuxis gazing blindly at Parrhasius’s curtain. The bobcats aren’t bobcats. They are taxidermic specimens, closer to stuffed handbags than to cunning killers. Photographically alive, they are technically dead. To see them as objects on display transforms the “homes” they haunt into mausoleums under construction. This purring paradox of the animal image stalks our backyards.

At first glance, Stein’s photograph Dead End Street (fig. I.5) seems to be about nothing in particular, in striking contrast to the other images in Domesticated, which abound with fawns, bears, canaries, foxes, bobcats, and other charismatic creatures. This image of a dead-end street, however, reveals something brutal in its banality. The natural scene appears wholly under human control. Manicured and monotonously green, the surrounding forest is as man-made as the human homes lining the paved streets, making us understand that images of nature are, in fact, unnatural. Posed on the edge of irony, Stein’s fox in a drainpipe (fig. I.1), one of numerous stuffed specimens, forces us to confront the limits of human understanding, specifically that of sight as the sense tied most closely to reason. Seeing and knowing are worlds apart. What do we really know about those houses? Perhaps there are people inside them. Maybe animals live in those woods and wild birds fly overhead. We do not know. We cannot see them. That uncertainty condemns us to know animals primarily through images.

“Ambiguity,” the art historian Ernst Gombrich declared, is “clearly the key to the whole problem of image reading.” The postmodern position exploits this ambiguity by stressing a fluid morphology in a Darwinian universe where neither human nor animal assumes a clear priority. In L’animal donc que je suis (The Animal That Therefore I Am), Jacques Derrida opens by acknowledging that he lives intimately with a cat, but his pet disappears pretty quickly. This swift abandonment reflects a prejudice of the Western philosophical tradition. From Descartes’s lions to Wittgenstein’s beetle in a box, animals illuminate the limits of human knowledge, a problem only augmented when images replace direct examination of these furtive, silent subjects. As Stein insists, there are no animals here, only human ideas about them. Even as animal studies has emerged as a new field of inquiry, ambiguities raised by this subject reside in cultural and historical conditions that, in everyday practice, are anything but clear.

The essays in Gorgeous Beasts face this challenge directly, taking up the urgent task of finding animals hiding in a politicized forest of images. Where there are images, there are animals. From cave paintings to computer graphics, from personal intimacies to political relations, from literature to philosophy, images of animals suffuse human cultures. Throughout history animals circulate as different forms of cultural currency. These essays both recover the histories that give rise to these representations and track the desires that conjure them, awakening us to worlds unrealized, where history and desire meet to create knowledge. Seeing animals historically reveals what we know about them without really knowing it. We may love animals, live with them, handle, harness, or hunt them, but often without much awareness of how they come to our call or to inhabit our hearts. Gorgeous Beasts tracks the signs that lead to a fuller awareness of such things, enriching our everyday appreciation of the animals in our midst.

But signs take us only so far. Images lead to bodies, the bright and fecund bodies of beasts. Pursuing signs of animal life, these essays recover the physical register of representation. Images make animal bodies visible, but those bodies make images matter. The material virility of animal life provides human cultures with untold resources. Animal bodies come to matter in myriad ways: as food, fetish, labor power, companion, art object, science specimen, even military weapon. Gorgeous Beasts examines their creative efficacy in human cultures, their various uses and abuses. Several essays, for instance, ponder the fate of animal bodies as food for humans. Whether hunted, harvested, or slaughtered, those bodies sustain life through relationships that far exceed representation. They raise an ethical dilemma linked to the self-appointed human place at the top of current culinary hierarchies. Just as interpretive assumptions and biases based on class, race, gender, and sexuality have received productive scrutiny, so too is anthropocentric privilege ripe for critical interrogation. Such inquiry involves unraveling a network of values in which animals persistently figure as embodiments of human desires in the name of “natural” priorities. Giorgio Agamben, Luc Ferry, and other recent cultural theorists take animal bodies as their territory. Gorgeous Beasts follows suit, advancing an ethical inquiry into the cultural destinies of animal bodies.

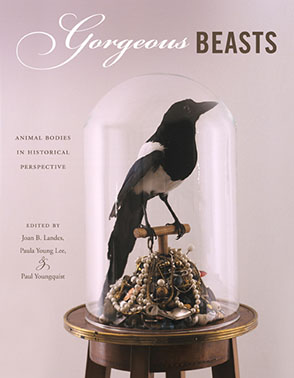

If animals matter ethically, why not artistically? Animals increasingly occasion creative activity that was once considered uniquely human. It isn’t simply that animals serve artists as objects. The golden calves and serial sharks of contemporary artist Damien Hirst reveal how drenched in lucre and violence animal art can be. Perhaps more interesting—because more moving (in all senses)—are artworks that arise as a direct effect of living (with) animal bodies. The work of artists Olly and Suzi is exemplary here: sharks co-create mixed media sculpture, or snakes collaborate as body painters. In these works, animals occasion artistic activity, which occurs in concert with humans. Something similar happens in the austere, thoughtful work of Mark Dion, featured in this volume. Animal bodies take many forms there: as pictures, taxidermy, toys, even vehicles (fig. I.6). Dion forces a reflection not simply on animal bodies but, more forcefully, on their appropriation by human institutions and their beautiful irreducibility to such uses. Representative in this regard is his mesmerizing magpie under glass, taxidermic and perched on a heap of jewelry, presumably of its own gathering (fig. I.7). Science stuffs this beast for display, true, but the beauty of its flashy feathers and the profusion of jewels beneath its feet wildly surpass its specimen status. The life of this animal body exceeds the terms of its representation. Such is the creativity of gorgeous beasts. They represent and disrupt human desires that would surmount them. Art such as Dion’s creates companionships among animals of wildly different varieties and potentials. Such is the exhilarating promise and prospect of living—and creating—with gorgeous beasts.

Are there lessons here? Do animal bodies enhance life? The following essays answer emphatically: yes. They offer few conclusions, perhaps, but promote a variety of perspectives from which to view animals, humans, and the many vital relations among them. If there is a general aspiration at play here, it is that living (with) animals might become a condition of cohabitation for us today. As cohabitants, animals conjure images. They incite knowledge. They configure relationships that yield companionship. They inspire ethics. They create art. “Becoming animal,” in the influential provocation of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, puts these cohabitations into motion and lives with the results. Gorgeous Beasts thus examines animals as kith and kin, with the cunning of serpents and the innocence of doves.

Even, at times, as foxes.

Bestiary

The essays gathered in this volume share a common concern with the cultural fecundity of animal bodies, but they speak from a wide variety of critical perspectives and historical contexts. The scientific study of animals is a surprisingly complex practice. In chapter 1, “Animal Subjects: Between Nature and Invention in Buffon’s Natural History Illustrations,” Joan Landes looks at the role that images play in the emergence of animal science. She begins in a surprising place: with Picasso’s illustrations of the Comte de Buffon’s monumental Histoire naturelle. Picasso’s images are striking for their abstract simplicity. In this they resemble those that originally accompanied Buffon’s eighteenth-century text, but for unexpected reasons. Buffon famously banished the mythical and the fantastic from the scientific treatment of animals. Scrupulously describing the austerity of his scientific method, Landes divides Buffon’s devotion into three principles: exact description of animals, comparison among their varieties, and their utilitarian proximity to humans. The upshot of Buffon’s naturalism was the depiction of animals less in their individuality than in their typicality, a sensibility that appealed to Picasso, who also sought to render animals in the abstract terms of an idealized type. Buffon’s monkey and Picasso’s bull share the typicality of their kind. Most profoundly, then, Landes’s essay advances a brief history of the naturalization of animals, their relocation from the realm of fantasy to that of natural science. In a neat finishing twist, she discovers the return of the repressed fantastical bodies in the beasties and cherubs at play in images framing the animal engravings accompanying Buffon’s Histoire.

In “Renaissance Animal Things,” the second chapter in this volume, Erica Fudge undertakes a courageous reversal of commonplace notions of Renaissance humanism. Working from the assumption that animals exist neither as objects nor as representations but as things capable of agency, she examines their effect on Renaissance life, in particular the intimate dramas of love. As active presences in the world, co-agents of the everyday, animals participate in life completely. But they do so in a peculiar manner, which Fudge captures in the phrase “animal-made-object,” signifying both an object made from an animal and an animal viewed as an object. Animals remain inseparable from the products they make possible, and this typically unacknowledged fact gives them a presence in the very products that seem to outlive them. Thus gloves made of dog skin, such as those of which Antonio Pérez writes to Lady Penelope Rich in the late sixteenth century, are not just signs of devotion but skins whose materiality calls doggedness to the cause of love. Similarly, the scent of the civet is more than a smell. It implicates its human wearer in animal life. Finally, at its most fearsome, the animal comes to denude the human, as in Shakespeare’s King Lear. The animal-made-thing undoes Lear’s privileged humanity, equating the breath of his beloved Cordelia with that of “a dog, a horse, a rat.” As living things, animals are cohabitants of a life that exceeds human reckoning.

These assumptions are directly challenged by the startling use of dogs as weapons of terror, as discussed in chapter 3, “The Cujo Effect.” Here, Paul Youngquist explores the transgressive transformation of a pet animal into an instrument of unspeakable horror. In the 1790s, the British decided to quell the Maroon uprising in Jamaica by deploying bloodhounds, trained by the Spanish to attack and eat black men, women, and children. Unleashed as instruments of war, the dogs were so repugnant that one British officer, witnessing such an attack on the neighboring island of St. Domingo (now Haiti), censored his own account, believing that to narrate the event accurately would be obscene. Translating the event into words would be to condone an act fundamentally incompatible with civilization, exposing the belief that white men were morally superior to black “savages” as a myth. But even the image of hounds tearing into infant flesh gives the lie to that delusion, for those dogs are extensions of human hands. Their sadistic acts reflect the perverted will of their masters. In The Animals Issue, philosopher Peter Carruthers makes the controversial case that animals have no direct moral claim on humans. Instead, he argues, human mistreatment of animals results in moral injury to the perpetrators, and that is reason enough for humans to treat all creatures well. The objections raised by the same British officer to using bloodhounds to terrorize Maroons in 1796 reverberate strangely with the deployment of military dogs today to terrify and humiliate enemy combatants, most infamously at Abu Ghraib prison in 2003 and 2004.

In chapter 4, “On Vulnerability: Studies from Life That Ought Not to Be Copied,” Ron Broglio explores other venues in which the animal is consumed and classified through violence. The setting here is late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain, where animal slaughter and harsh working conditions were a feature of the rural landscape banished by those who wished to present a bucolic vision of rustic labor. Juxtaposing peasant poetry, visual and literary picturesque accounts of the English countryside, and agricultural treatises, Broglio ponders how the apparatus of death was “tastefully” omitted from public view. “Not to be copied”—a phrase that appears in an 1806 encyclopedia of images of the daily tasks of rural peasant life—is an injunction against viewing the act of animal slaughter. Without simplifying the connections between human and animal suffering, Broglio explores the link between labor, livestock, and English liberty, and posits the shared vulnerability of tenant farmers and animals under conditions of bare subsistence. In the process, he reveals a great deal about the social class order underpinning British wealth, starkly separating the lives of the rural gentry and urban elites from the poor.

Social class divisions were further compounded by emerging racial hierarchies during this period, as shown by Pierre Serna in chapter 5, “The Rights of Man and the Rights of Animality at the End of the Eighteenth Century.” In revolutionary France even more dramatically than in England, owing to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789, new questions arose as to how to expand or limit the universality of rights, not only for all members of the human race but implicitly—as some began to discern—for all sentient beings. Are animals political subjects, Serna asks, and, if so, what would such a claim imply? “Animality” raises the broader question of our own animal nature, which Serna traces in philosophical and scientific queries about the nature of life. Opportunities for the expansion of rights contracted between 1795 and 1799 during the more conservative years of republican rule under the Directory, and especially following the imposition of military rule by Napoleon in 1799. In the French colonies, Napoleon reimposed slavery after it had been abolished in 1794 during the radical phase of the French Revolution. At home, democratic rights were curtailed and class divisions hardened. In the increasingly prestigious scientific fields of natural history and comparative anatomy, Serna charts a parallel movement from more egalitarian to more hierarchical views. Educational reformers under the republic and the empire aimed to place knowledge at the service of the nation, and science was accorded a privileged place within republican and imperial institutions. Ultimately, however, hierarchical principles of harmony, order, and utility in the life sciences foreclosed possibilities for more egalitarian thinking about humans, animals, and nature as an ensemble of similarities and differences. Paradoxically, too, the most advanced democratic thinkers sometimes sacrificed the rights of animals in their effort to expand the liberty of men, irrespective of their race or class.

What of animals in cages? For all intents and purposes, zoo animals are tame, radically altered by their unnatural setting. Yet they are still coded as “wild,” for the state of being wild has become, as Harriet Ritvo notes in chapter 6, “Calling the Wild,” more “a matter of assertion than of description.” Zoos provide institutional proof of the currency of such assertions, for the idea of wildness is remarkably knotty, tied up with law, literature, and aesthetics. It is also linked to the history of scientific classification, which now ties the assertion of an authentic “wild” ancestor to the genetic preservation of animal kinds. Such assertions are inevitably political, and for animals, their consequences can mean death. Starting with the gray wolf and ending with the domestic dog, Ritvo examines the epistemological conditions of the fraught history of human encounters with animals. Her essay surveys “wildness” as connected to cultural myths of the environment, while illuminating the difficulties of understanding the condition of being wild. Is it a state, a species, a location, or a behavior? The problem she parses is lodged in language, the tool scholars and scientists necessarily use to make sense of their subject. The very act of writing about animals contains them as surely and insidiously as the bars of a cage. Is a zebra a white animal with black stripes, or a black animal with white stripes? The question becomes ironic when posed as black words on a white page.

Nigel Rothfels analyzes trophy hunting in chapter 7, “Trophies and Taxidermy,” suggesting that the theatrical staging of human events, or the apparatus of the play, provides a cultural corrective to a fearful state of uncertainty. His chapter might be subtitled “101 Uses for a Dead Elephant.” Insofar as “a dead elephant is not, in fact, the sort of thing one can do anything with terribly easily,” Rothfels’s approach offers a welcome note of absurdity. He makes the point that elephants have long been sought by trophy hunters, typically men of power and privilege who pursued them, shot them, killed them, and stuffed them, all in order to be photographed with them, thereby constructing a superior self-image while selling a personal mythology to the masses. Hunted, the elephant is “wild” merely because the narrative demands it. Rothfels opens his chapter, however, by discussing an installation video, Play Dead; Real Time, by artist Douglas Gordon that features a trained elephant “playing dead” and performing other tricks. Inside the gallery setting, the elephant is not wild. Rather, it embodies its own secret memories, even as it serves as a cultural repository. Not comic so much as “funny,” Gordon’s video radically separates the animal from its wild origins and makes it perform in a way that is subversive or “queer,” knowing full well that the sexualized mythology of game animals enhances their mystique. Even their deaths become an occasion for reflection. Rothfels closes his essay with a stirring meditation on trophy photography as a medium of doubt in which a dead or dying animal provokes the human attempt to make sense of mortal violence.

The vexed legacy of scientific encounters with animal life is far from resolved, as Sajay Samuel and Dean Bavington demonstrate in chapter 8, “Fishing for Biomass.” Addressing the dramatic collapse in 1992 of what had been the world’s largest ground fishery in the waters off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, Samuel and Bavington link the disappearance of the wild codfish to the elimination of a nearly five-hundred-year-old way of life among the fishing communities of eastern Canada. With chilling lessons to be drawn for global practices of overfishing the oceans and destroying wetlands around coastal communities, the authors describe how the same techno-scientific management of wild codfish, fishermen, and the oceans, tied to capitalist exploitation of the fishing grounds, is paradoxically still being offered as the primary solution to the problem it created. Scientific representations of fish as populations or biomass, of fishermen as labor or rational economic actors, and of oceans as private or public property were harnessed to increasingly potent fishing technologies such as gill nets and bottom draggers. After more than a century in the techno-scientific crucible into which they disappeared, the once wild codfish has been resurrected as industrial biomass. Simultaneously, fishermen have been transformed into professionalized harvesters and the seas transmogrified into watery farmlands. In contrast to what they term the “algebraic machines of capital and techno-science,” the authors expose the limits of knowledge systems tied to classification and marketing of fish in the commodity form of biomass, which denigrates the vernacular ways of fishermen, who once respected the fish.

Chapter 9, “Daniel Spoerri’s Carnival of Animals,” Cecilia Novero’s probing exploration of neo-avant-garde artist Daniel Spoerri’s animal assemblages, Le Carnaval des Animaux (1995), brings us full circle: back to the early modern period by way of Spoerri’s recycling of the influential artist and art theorist Charles Le Brun’s comparative physiognomic drawings of animal and human heads, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus’s classificatory systems of animals, and Darwin’s notion of evolutionary time. Spoerri’s Carnival animals, as Novero reveals, take flight through the undoing of distinctions that separate humans from nature and from animals. Spoerri’s work calls upon the centuries-old popular resources of Carnival, where laughter and black humor are tied to strategies of inversion (of high and low, human and animal, death and rebirth). By decontextualizing quotidian articles like coat racks, fur coats, mementoes, folkloric masks, scientific instruments, and taxidermic animal bodies, Spoerri challenges the protocols of representation, perspective, and illusion that secure the privileged domain of high art. In the carnivalesque moment where time and space are interrupted, the possibility is realized for undoing the images of animals that humans have created to surmount their own limitations and fears.

The final section of Gorgeous Beasts presents the reflections of artist Mark Dion on animals and the desires and histories that shape human encounters with them. As a kind of coda to the volume, this section puts into play many of the issues raised here—with the studious playfulness that characterizes so much of Dion’s oeuvre. Whether the head of a rhinoceros, a plastic-wrapped bear in a packing crate, tarred animal bodies hanging from a dead tree, or a toy bear holding a boom box in its mouth, Dion’s images of animals always give way to complex networks of the desires and discourses that make them visible. Animal bodies appear as nodes of value in cultural systems they both vindicate and indict: relics in transit, specimens on display, victims of disaster, even forms of entertainment. The “marvelous museum” of Dion’s work wrests unexpected meanings from animal bodies. They come wrapped in history and desire, and the joy of almost any Dion installation or exhibition is the opportunity it provides to reflect on their cultural vitality. In the interview that accompanies his images, Dion addresses many of the same concerns that the authors of Gorgeous Beasts explore, but from the perspective of a contemporary artist. Historical curiosity about the wildness of the wolf, for instance, burgeons into contemporary critique of its commodification. The past falls artfully into a present wholly configured by capital and techno-science. Dion’s art and reflection, however, provide grounds for hope that human encounters with animal bodies can change lives for the better and revitalize the world.

Such is the hope of the essays gathered in Gorgeous Beasts. They find promise in animal encounters like a recent one with a whale named Tilikum. On 24 February 2010, news outlets reported the shocking death of an experienced forty-year-old female trainer caused by a twelve-thousand-pound orca, or so-called killer whale, at the SeaWorld park in Orlando, Florida. Tilikum, a male or bull whale, had lived at the park since 1992, one of eight orcas at that location. The incident marked the third time the animal had been implicated in a human death, and on this occasion numerous audience members witnessed the event. A SeaWorld spokesman acknowledged Tilikum’s involvement in the 1991 death of a trainer after she fell in the pool at Sealand of the Pacific, near Victoria, British Columbia. In 1999, SeaWorld security found the body of a man—who either jumped, fell, or was pulled into frigid water and died of hypothermia—draped over the whale. In the latest incident, the female trainer also drowned, after being thrashed in the water by Tilikum (nothing “carnivorous” occurred). There were conflicting initial reports of the event. What is more, one spectator “said he heard that during an earlier show the whale was not responding to directions. Others who attended the earlier show said the whale was behaving like an ornery child.” Yet it was later confirmed that although the trainer was pulled underwater by her long ponytail, she was “interacting” with the whale in the water when the incident occurred.

Alongside the terrible loss suffered by the friends, family, and colleagues of the dead trainer, this event points to larger cultural narratives about wild animals used in circuslike routines and their exploitation for profit. It poses the question of animal nature, of what it means to train, breed, and display a wild animal. It asks whether an undomesticated animal’s behavior can legitimately be described as infantile disobedience. It raises the issue of where animals are—and ought—to be found: in this case, in a containment cage or a vast ocean, performing according to a demanding schedule, or swimming freely? And it invites speculation on the implicit violence accompanying the ownership and control of animal life. Even the name “killer whale” calls up the violence against which humans measure their superiority to animals.

The Florida park where the incident occurred was owned by the Blackstone Group, a private equity company that also owned part of the Universal Orlando theme park. As the accounts further attest, the whale was purchased from a Canadian facility. As such, Tilikum was a commodity bought and sold within a global trade network that furnishes “wild” animals from marine and land habitats to parks, zoos, aquariums, and even private owners. Certainly, some members of the public uttered facetious disappointment at having missed witnessing firsthand the raw spectacle of the trainer’s death, while others cleverly called this animal a “serial killer whale,” or more gruesomely regretted not having “fileted and fast food[ed] it” upon its first kill, proposing “Fish sticks for everyone!” or “Sushi time?” However, most web posts defended the whale and strenuously condemned those who would force a “wild” animal to submit to a circus routine. Concern was also expressed about the inability of trainers to interpret the animal’s truculent behavior as a sign of resistance to exploitive show routines, or even as an expression of psychological malaise or physical illness. Paradoxically, the orca was defended for acting both according to its nature (presumably “killing”) and against its nature (performing routines). As one blogger put it, “I don’t know of any cases of humans being attacked by killer whales in the ocean.” Indeed, the majority of the commentators seemed to echo one writer’s poignant call to “please put the whale back into the ocean where it belongs!!! FREE TILLY,” or another’s conclusion that “it’s not the whale’s fault, it’s ours, Humans.” Doubtless for their own reasons, not least their substantial investment in the animal, SeaWorld officials subsequently announced that they would spare the life of Tilikum. The chief of animal training at SeaWorld parks stated that “Tilikum would not survive in the wild because he has been captive for so long, and that destroying the animal is not an option either, because he is an important part of the breeding program at SeaWorld and a companion to the seven other killer whales there.”

The whale’s saga did not end there, however. Following a yearlong hiatus after what is described as “his last killing,” in March 2011 Tilikum was returned to performing at SeaWorld Orlando, too valuable a commodity to be allowed to retire. That Tilikum and his trainer shared the enclosed space of a containment tank was not an accident. It was a product not only of the intersecting histories of this animal and this particular woman but also of the intersecting history of this species of cetacean (the orca is the largest member of the dolphin family) and the human species—all of which created the conditions for an animal show before a paying public, eager to see with their own eyes a beast that has gone by other names in our cultural imaginations and belief, from the biblical sea monster Leviathan, to the ruler or custodian of the sea and benefactor of humans, according to indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

Whether viewed as those of a sea beast or of an otherworldly benefactor, Tilikum’s actions appear as a failed attempt at cross-species communication and kindness, of which the sixteenth-century French author Michel de Montaigne thought animals capable. As he famously remarked in “An Apologie of Raymond Sebond,” “By one kinde of barking of a dogge, the horse knoweth he is angrie; by another voice of his, he is nothing dismaid. Even in beasts that have no voice at all, by the reciprocall kindnesse which we see in them, we easily inferre there is some other meane of entercommunication: their jestures treat, and their motions discourse. . . . Silence also hath a way, Words and prayers to convay.”

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.