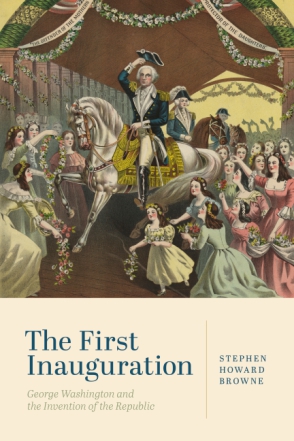

The First Inauguration

George Washington and the Invention of the Republic

Stephen Howard Browne

The First Inauguration

George Washington and the Invention of the Republic

Stephen Howard Browne

“Browne skillfully synthesizes biography, travelogue, social and political history, and rhetorical analysis to reach fresh conclusions about the relationship between individual and national character.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

In this book, distinguished scholar of early America Stephen Howard Browne

chronicles the efforts of the first president of the United States of America to unite the nation through ceremony, celebrations, and oratory. The story follows Washington on his journey from Mount Vernon to the site of the inauguration in Manhattan, recounting the festivities—speeches, parades, dances, music, food, and flag-waving—that greeted the president-elect along the way. Considering the persuasive power of this procession, Browne captures in detail the pageantry, anxiety, and spirit of the nation to arrive at a more nuanced and richly textured perspective on what it took to launch the modern republican state.Compellingly written and artfully argued, The First Inauguration tells the story of the early republic—and of a president who, by his words and comportment, provides a model of leadership and democratic governance for today.

“Browne skillfully synthesizes biography, travelogue, social and political history, and rhetorical analysis to reach fresh conclusions about the relationship between individual and national character.”

“A paean to the country’s past as well as its ever-present possibility.”

“Browne’s analysis of Washington’s address is superb. He succeeds admirably in showing how Americans performed and instantiated a dynamic, protean conception of nationhood.”

“A very interesting topic. The idea of employing Washington’s trip from Mount Vernon to New York City as a way of demonstrating his commitment to republicanism is inherently fascinating. So much has been written and published about Washington over the decades that it’s hard to find a niche where something worthy of public attention has become available.”

“There is much to praise in The First Inauguration, which uses detailed historical reconstruction of George Washington’s journey to the first inauguration ceremony in New York and careful analysis of his inaugural address, as well as celebrations of the anniversary of those events, to draw conclusions about the creation of American identity, along with the development of American civil religion, American exceptionalism, and democratic rhetorical norms. Browne’s writing is engaging, and his reconstruction of Washington’s journey is impressive.”

“A masterful analysis.”

Stephen Howard Browne is Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State University. Learn more at www.stephenhbrowne.com.

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The Things He Carried with Him

2. On the Road to Philadelphia

3. Between Past and Future: Trenton & Beyond

4. His Excellency Arrives in New York City

5. Sacred Fire of Liberty: The First Inaugural Address

6. The Inauguration in American Memory

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

I aim in this book to tell the story of George Washington’s journey to New York, of the speech he gave on April 30, 1789, and of the speech’s legacy in the American tradition. The first inaugural address is this story’s centerpiece. My analysis of it is designed to illustrate this simple but necessary thesis: that Washington’s performance that day established a resource for the ongoing work of realizing America’s greatest ideals. That the address has not been sufficiently recognized or availed of for this end is regrettable but not irremediable. Here, I hope to reassert the inaugural address’s claim to place in the American canon of state papers—to remind us that we have in the address and in the circumstances of its delivery a rich and vital fund for thinking about the political situation in our own challenging times.

The First Inauguration is written for a readership concerned with the tenor of political discourse in our own time. Americans have always been a noisy, clamorous people. We do not shy away from debate; indeed, we seem to thrive on it as the very stuff and substance of democracy. When such give-and-take is thought to be productive, sincere, and motivated by rival conceptions of the public good, we applaud; when it appears merely partisan or self-interested, we despair. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Henry Clay; Abraham Lincoln, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Martin Luther King Jr.—titans all, and we claim them with pride as our own. Constitutional conventions, civil rights marches, declarations of independence: such eloquence. But more often, and certainly of late, we lament the passing of an age when citizens deliberated as citizens, with speeches, not tweets; with crisply argued letters to the editor, pamphlets, orations, and finely tuned sermons. That is nostalgia, but the longing is real. And still, an unmistakable note of despair may be heard, as if we have somehow lost something precious, hard, and fine about our shared humanity. Have we?

We have not. I hope to provide in the following pages a reason to believe again in ourselves, in our leaders, and in the essential dignity of the democratic quest. To those who might wonder whether yet another book on Washington is needed, I respond with a resounding yes. We need to call to mind the story of Washington’s inauguration because in it we discover vital resources for the reanimation of civic life; we need, like every generation, to invent a version of the first president to meet our own particular but hardly unique challenges. We need to listen to what he has to say because what he said and how he said it offers us a gift we cannot afford to ignore or cynically dismiss.

We are, I trust, beyond the point where apologies need be made for the Founders. No one now sensibly denies their shortcomings, their racial and gendered assumptions, or their hypocrisy, elitism, and assorted privileges. Few now are inclined to give them a pass, nor should we. They were not saints and ought not to be regarded as such. Neither were they devils. My general approach to Washington is to acknowledge his humanity, and so his sins; to focus on the best of who he was and what he said; and to suggest, along the way, that we may well benefit in our time from paying attention. The first president has always served as a screen on which Americans have projected preferred versions of themselves. In this sense, we can choose our parents. We can summon Washington again to remind us that we can do this, that the American experiment in republican democracy is still worthwhile, and that in his speech and behavior may be found an exemplar of what Americans may sound like again.

Even if one grants that another study of Washington is thus warranted, it may not be evident that a single speech could so significantly shape the political culture of a new nation. This is a genuine consideration, and I will offer several reasons why I think the speech can and should have such an impact. Washington is a rarity in that though he was often thought reserved, he was in fact a man of words—lots of them. We may with confidence presume that when he spoke, he did so to a purpose, and he meant what he said. The inaugural address, written with the assistance of James Madison, was and remains highly sensitive to the exigencies of its time and place of delivery. At the same time, it shares in the Founders’ preoccupation with the future; it was thus composed as well for a generation not yet born. By studying it carefully, we learn how to read in its message the fundamental principles of republican government and its call to Americans to become better versions of themselves. The address contains within itself the great and abiding questions of national identity: What values are necessary for a people to launch such a government? What ought its leadership to sound like? What is the place, if any, for such old-fashioned ideas as virtue in the new order of things? What, finally, are the ties that bind so strong as to unite a rapidly growing, highly diverse, and aspirant people? These questions will guide our efforts to reclaim Washington and his address for the civic imagination.

What then might we learn by considering Washington’s address and the events around it? A great deal, for in these events we glimpse what the creation of the American republic looked and sounded like; we discover a people announcing themselves and affirming their vision of what a truly republican leader ought to look and sound like. This exercise of our political imagination can allow us to see today what all this might have looked like in the process of becoming. The inauguration was not the first or only such natal moment, but it was unquestionably a key phase in the early constitution of what it meant to be an American.

An extraordinary amount of scholarship surrounding Washington is available in biographies, histories, and political theory. I have leaned heavily on it in the pages that follow, including such standards as provided by Douglas Southall Freeman, James Flexner, Joseph Ellis, and James Alden, as well as the marvelous resources to be found in Washington’s correspondence. Without presuming too much and hoping to offer the reader a brief but instructive account of the inauguration, I have sought here to ground basic issues of republican government in just a single text—Washington’s first inaugural address. The payoff, I hope, is to equip the reader with a deeper sense of what was at stake at the nation’s inaugural moment, how Americans chose to participate in it, and ultimately, what we may learn from that moment to forge ahead.

To date, no such work on the inaugural address has appeared in print. Histories of Washington typically include a few pages on the inaugural day and move on to presumably more important matters of statecraft and congressional wrangling over titles, taxes, and others affairs of governance. This is unfortunate given the significance of the event and its dynamic interplay of ideas, personalities, and symbols. My work in rhetorical studies allows me to home in on the rich variety of symbolic and material resources that helped give to this event its abiding importance. In addition, I attend to the rituals of nationhood borrowed and created along the way and to the meaning and force of such popular activities as parades, dances, visual performances, speeches, and balls. At the same time, I will put these ephemera within the context of the political thought and controversy characteristic of the time.

More than anyone alive, George Washington appreciated the utter novelty of the circumstances that would soon usher him into office, far from Mount Vernon’s vines and fig trees. No people on earth, ever, had dared invent a system of government quite like the one he was now to lead. None dared, not even now, to imagine that it would all work as planned. So many issues remained unresolved; too many of his fellow citizens remained doubtful, some bent, perhaps, on the great experiment’s ultimate failure. Forces, only yet glimpsed, threatened, not only at home but also abroad, in a world deeply suspicious of the extraordinary human and natural resources now organized under the sovereign powers of a republican nation. Who now counted as friends? Who now as enemies? These matters would have to be sorted out, and quickly. The presidency itself was without precedent, conjured up in the final weeks of the Constitutional Convention—not an afterthought, to be sure, but commanding surprisingly little in the way of heat or deep reflection. What was to become of him, of his country?

Perhaps—we cannot know this—George Washington asked himself the toughest question of all: Why? Why assume such responsibilities now? On the back side of his fifties now, he had lived several lifetimes in an age when men of his stature had every right to assume the prerogatives of success. Washington’s health was sound, providentially so after the endless miles, the battles, and the camp contagions that conspired to lay down most mortals. It was not too much to ask that he now be granted the rewards all agreed were his: some privacy, time to ride, hunt, do a little fishing; dinner with Martha, a glass of Madeira with friends. Like many squires of his station, Washington looked forward to improving his estate—his financial affairs, certainly, but above all Mount Vernon, the house, its farms, the potential that had not yet been brought to fruition. He was never a particularly successful farmer, not really. That could change. His investment schemes had not yielded nearly what he had hoped; that, too, might be improved on. It was all right there—the land, the river, the enslaved and hired help. The general was a reserved man, true, but he needed company and was indeed hardly ever without it. Alexandria was just down the road. Here, too, all was just as he wished: visitors and the curious might circulate through the estate, have a bite, and talk of the day. When that was enough, the patriarch would excuse himself and retire upstairs. Perfect.

Why then? Motive is a notoriously elusive thing, fugitive, and not always to be trusted even when found. The question still seems worth asking, not so much for psychological insight as for what it might suggest about the inauguration and indeed about the national heritage. Perhaps the most efficient route to something approaching an “answer” is through the elimination of standard interests. These, too, are telling. Why does anyone contemplate political office? Ambition, of course, but ambition for what? Power comes first to mind, but that does not tell us much either. It is not clear what about the executive office circa 1789 could possibly have been appealing to a man motivated by power alone. History tells us, too often, that tyrants surely must aspire to more promising heights than this. History tells us, too, that high office can serve as a useful means to wealth, emoluments, the high life! Not here, not now, and not by a long shot. Well, then, military glory: the record will show a long and benighted tradition to this day and doubtless beyond that executives—monarchs, kings, and despots—have always eyed politics as a path to martial ends. Again, America, 1789: what military? There was no standing army as such, no navy; a few posts spread along a massive western frontier. Not exactly a tempting object of desire for the would-be Caesar.

Then again, maybe it was just about fame. Granting even the above disincentives, we can readily understand enticements to office for those who see in it a way to satisfy some deep, if otherwise inexplicable, need for the affirmation of others. Celebrity candidates, we might call them today, see office as a kind of extension of their own brand of entertainment. What they cannot deliver by way of ideas may be compensated by pleasures of the spectacle. And yet a man would have to be desperate indeed in the nation’s founding age to seek office for such reasons. Fame is complex and historically variable, and it drove men of the time as it has men of all times. Washington was deeply attuned to its chords, and he danced, beautifully, to its call. As strange as it may sound to us now, however, the executive office of a new government, of a fledgling republic, pitched precariously on the edge of the west Atlantic, numbering about three million souls stretched from New Hampshire to Georgia, simply was no place for a man craving attention.

George Washington, Esquire, needed none of this, wanted none. That he was ambitious and made of stern stuff there can be no doubt. He understood power as did few others; he was comfortable with it, used it with little evidence of regret. Men had died at his command; he held hundreds of fellow human beings in bondage. Washington did not seek power, because he already had it; he was power. It is inconceivable that he assented to the presidency because he wanted more; if anything, the office could only mean less. As for wealth and its trappings, little needs to be said, because so little was in the offing. Washington was, of course, a very rich man by standard metrics of the day, and money is for the poor, after all. He asked for none in war, and got his way; he will ask again, and be denied. Office will mean for Washington not the way to wealth, but away from it. We may wonder, in turn, what it would even mean to seek after Washington’s motives in the way of military ambition. The very question would be absurd if the record were not so grim, the men on horseback so frequently cresting the horizons, ready. That Americans have been spared the trauma of the military coup d’état is owing in no small part to a general insistent on the privilege of civil authority, who, wielding the sword in battle, laid it down in peace and left it there.

If not fame, then, if not power, money, or military might, then why was the master of Mount Vernon pacing its floors on the morning of April 16, 1789, bags packed? The answer, of course, is duty. This much can be no surprise: readers with the most fleeting familiarity of our subject know that Washington had made a career, a life, shaped by the requirements of service to others, to his country above all. He could be imperious, especially in younger days; his appetite for land, especially, was voracious; he would always be exceptionally sensitive to reputation. He had his blind spots. He was human, and then some. But from early manhood in the woods of western Pennsylvania, to the verdant expanses of Virginia’s Northern Neck, the fields of battle, and Philadelphia, one constant provided coherence and force to this most singular of men. Duty was for Washington never a choice; it was ingredient to his being.

He left Mount Vernon because that was what it meant to be George Washington. The tautology may be forgiven if we remind ourselves of this fact: for the president-elect, as for his fellow citizens, the prospects of republican success presupposed the triumph of character. Now, character meant above all a capacity to act well on behalf of the public good. It was a virtue and thus an attribute of the individual, but the self alone could by no means circumscribe character. It only had meaning and force when exercised for others, and this required a very serious and very demanding sense of duty. And no one, safe to say, commanded such resources of character, such a commitment to the commonwealth, as the man now clambering into the carriage that would take him, at length, to Federal Hall.

Something of the method at work in this project may be suggested by the image of a road trip. By way of situating the event within its lived experience, I first take the reader on a journey from Mount Vernon to Manhattan in the Spring of 1789. Along the way, we will stop, as Washington did, in Alexandria, Virginia; Baltimore; Wilmington, Delaware; Philadelphia; Elizabeth-Town, New Jersey; and finally accompany him off the boat and into New York City. The point here is to capture in the image of the individual the forward direction of a people at large, to recover the pageantry and anxiety, to listen to the music, oratory, and acclaim, to ask who was left out and why, and to arrive, one hopes, at a more richly textured, nuanced, and instructive perspective on what it means to launch a nation.

The second phase of the project situates us in the New York City of 1789. Here we undertake to discover the various individuals—white elites, African Americans, the laboring poor—who gave to that time and place its distinctive claim on the American imagination. How and why they mobilized to greet and host the new president and government can tell us a great deal about how power in such contexts is articulated, staged, and given maximum persuasive force. The celebrations, parades, dances, music, fashions, food and drink, taverns, ballrooms, churches: all help tell the story of the early, early republic.

The third phase entails restaging the inaugural speech itself. Why this address has not received the attention it deserves, I can only speculate. Even if it were thought a poor production, it is after all the first such effort in American history; that should be worth something. The truth of the matter, however, is that the speech is quite good—indeed, a commanding statement on what the American presidency ought to look and sound like. We will see that the first of our presidential inaugural addresses is, as well, deeply reflective of the man giving it voice, and reflective, too, of the people who made it possible, listened to it, read it, and received its message in trust. The aim here, to be clear, is certainly not to make a case for Washington as a great orator; this he never was, and it would be foolish to claim otherwise. Nor is it to present dramatic new evidence of the speech’s abiding influence. The point is rather to demonstrate that it merits and rewards more than we have suspected. There is, I think, considerable yield here if successful: rather than tend exclusively toward either a social or a straight political history of the subject, I hope to synthesize both into a compelling account of how ideas get put into action and of how symbols are made concrete in the service of consolidating power.

Scholarly and popular interest in the founding of America continues to grow, and this project seeks to enter this lively terrain directly. The best work on the subject successfully integrates social, political, historical, and conceptual analysis into comprehensive accounts. Among the most noteworthy treatments, from which I have learned a great deal and for which I remain deeply grateful, are David Waldstreicher’s In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820; Sandra Gustafson’s Eloquence Is Power: Oratory and Performance in Early America; Simon Newman’s Parades and the Politics of the Street: Festive Culture in the Early American Republic; works by Stephen Lucas and by Pauline Maier; and anything by Jack Rakove. These distinguished scholars of the period, so different in approach and design, have materially assisted in my own attempts to give voice to early republican culture. A set of key terms grounds this study. My definitions are, of course, provisional and stipulative, but I think they are responsible to the scholarship and not eccentric to established traditions of usage.

Rhetorical studies strike me as most interesting and useful when they capture something of the noise, drama, and interplay of human agents doing important things in complex circumstances. Drawing on methods of rhetorical studies, this book offers a compelling story of this nation’s signal moment of symbolic birth. Rhetoric refers to the art of managing symbols in public contexts to persuasive ends. As both a human practice and a study of that practice, rhetoric has enjoyed a long-standing status in Western letters, dating back at least to ancient Athens. The art was understood by its earliest professors in several ways that bear directly on my account of Washington’s inaugural address. Although examined in different ways to several ends, early thinkers agreed that rhetoric attended most clearly to the basic act of speaking in contexts of civic life about matters of common concern. Teachers of the craft, including Aristotle, Isocrates, Cicero, and Quintilian, accordingly, sought to train their students in the invention, organization, stylistic treatment, delivery, and memory necessary for effective public speech. All appreciated that language was power or at least that the skillful management of it was, and that such power was crucial for the vitality of life in public contexts.

The Atlantic eighteenth century remained deeply beholden to these classical antecedents. Anglo-American treatises and educational curricula routinely featured precepts handed down from antiquity, especially by Cicero and Quintilian, and even—especially—prominent political, legal, and religious figures looked to them for guidance. The rhetorical landscape, so to speak, was of course dramatically different: white Americans were relatively more literate than most peoples on earth; enjoyed a flourishing, indeed quite remarkable print culture; and expected those who assumed the dais to respect their expectations for the dignity of the art. At the same time, the scope and function of rhetoric expanded to meet the diversifying and increasingly complex demands of early modernity. Today, we include within its ambit any manner of symbolic expression, including visual, material, and sensate artifacts. For the purposes of this study, I examine not only the oratorical performances of Washington and others, but also the persuasive work attendant to festivals, parades, clothing, and related evidence of creative expression designed to persuasive ends. This commitment leads me to our second key term.

Ritual, too, shares with rhetoric a long and rich history and a protean and sometimes elusive set of meanings. From anthropology to religion to politics and beyond, it has been employed across a diverse range of human practices; this, because humans seem if not by nature then by long habit deeply ritualistic animals. We need rituals. Why? Because recurrent form helps stabilize and give shape, meaning, and direction in a world otherwise uncertain and uncontrolled. We know this at the level of individual and private practice: the daily routine that, while seemingly banal, in truth helps establish our rhythms of life and provides the familiar and intelligible terms with which we make sense of the world, of our place within it. It is no wonder, then, that humans under conditions of abjection will seize on apparently trivial rituals of self-care—shaving in solitary confinement—to reaffirm their essential selfhood. We avail ourselves of the powers of ritual because they work.

How do rituals work? For the limited purposes of this study, I employ the term in no especially nuanced way to draw attention to their public functions. These functions help explain at least three persistent features of our story: change, identity, and memory. Students of rituals have long observed that they seem especially conspicuous during moments of transition—liminal episodes in the career of a people confronting change in some fundamental sense. We appeal to rituals under such conditions because they help us over the thresholds, give us a hand, so to speak, give us courage to leave behind what must be left behind, and brace us for the coming time. We need such assistance because these moments put our identity as risk; rituals have always promised to reaffirm who we are between past and future. Not that our shared identity is ever truly certain or fixed; finding ourselves on the other side of that threshold, facing new worlds, we seek confirmation through rituals as a means to remember who we are, and why. Like all peoples, Americans have drawn from and contributed to an enormously rich repertoire of such practices, not least among them inaugurations, festivals, and anniversaries. Now, this does not mean that we respond to such rituals as may be intended, and it seems not merely cynical to observe that our enthusiasm for celebrating shared pasts has waned considerably of late. Is it time for a rejuvenation? I think so.

A third term: virtue. We do not use it much these days, not in contexts of public and political life. This is regrettable. Is it surprising? The term is confessedly old-fashioned and frankly has never been used with great precision or consistency. Moral philosophers continue to exercise its potential for explaining, if not actual behavior, then its prospects as a standard for judgment and right action. As a political concept, virtue has been the object of over two thousand years of contemplation, from Aristotle to Alastair McIntyre. But what does it mean? That is, again, an unanswerable question, at least to satisfaction; here, I operate under the assumption that, as with all words, it means what a given people want it to mean. During the period under investigation, most people understood virtue as describing a certain quality of character made intelligible by the willing capacity to superordinate the public good above the private. The term, certainly, presupposes a number of complex assumptions about human agency, the relationship of the subject/citizen to the state, and the nature of political obligation.

I will attempt in this book to honor these premises as they operate in late eighteenth-century American culture. The more specific aim, however, is to focus less on the denotative meaning of virtue than on how it gets performed within the contexts of civic life and how it is ritualized and given rhetorical force. The analysis accordingly seeks to integrate what ought not to be left isolated; seeks, that is, to understand the work of virtue as it is performed by both massed citizens and by their chosen representative. The promise of republican government in 1789, as I understand it, was that America could have it both ways: that it could be governed through an exquisitely designed system without giving up the human element. System without agency is bureaucracy, and no way to run a nation-state; agency without system is tyranny. My thesis, then, is that Washington inaugurated a set of commitments that made it possible to have it both ways. He did so by instantiating an ideal of political virtue that simultaneously respected the systematic rule of law as established in the Constitution, and embodied the human values giving that system its ultimate rationale.

A few words, finally, about the man himself. Anyone writing about Washington in our time faces certain challenges, which, if not unique, must be confronted at the outset. Aside from Lincoln, no figure in American history has received more attention; none has been the object of so much hagiography and myth, no one so monumentalized into the collective consciousness as His Excellency. Scholarly treatments of Washington’s participation in this process, especially Stephen Brumwell’s George Washington: Gentleman Warrior, Paul Longmore’s The Invention of George Washington, Barry Schwartz’s George Washington: The Making of an American Symbol, and Gary Wills’s Cincinnatus: George Washington and the Enlightenment have demonstrated to striking effect the creation of Washington as a cultural symbol. There are compelling reasons for this apotheosis; indeed, the not very subtle subtext of this book is its promotion of Washington as a rich and relevant resource for thinking about Washington in the current age. Dangers lie afoot, not only of presentism but also of reproducing the excesses and distortions so long associated with our subject. Then again, we live in a time when it is hardly a given that a slave-owning, white, male elite ought to make any kind of claim on our convictions. Have we not had quite enough of George Washington?

No, we have not. Every generation of Americans needs to figure out its relationship to the past, and Washington is inescapably central to that past. He will not, cannot be made to disappear. The more difficult, pressing question is how to make him matter again. Again, I have tried in the following pages to avoid as much as possible any genuflections to his person on the one hand or any cheap shots at his quite real shortcomings on the other. I can only trust that by now we are beyond such mindless reflexes. My efforts bend rather to identifying the interplay of individual character and ritualized social action; this dynamic in turn helps us understand one of the ways, at least, that Americans inaugurated themselves into nationhood. The values enshrined as Washington’s own—his sense of responsibility to the common good, his rectitude and basic decency, his courage and restraint, his love of country—were thus delivered to a common inheritance and made the fit objects of our highest ideals as a republican people.

Considerations of method are seldom as riveting to the reader as to the author. Again, I will be brief. The story of Washington’s inauguration is multitextured and admits of no single reading practice. By habit and inclination, I lean toward sustained analysis of speech texts; this appetite is met by the account of the address delivered on April 30, 1789. At the same time, I am insistent that we attend to the many interesting and important modes of articulation that accompany, indeed make possible, the events surrounding that speech. To this end, we will want to look closely at the constituents of ritual, including parades, toasts, music, and so on. The general aim is to take these forms seriously without over reading, let theory inform but not bully the analysis, and fold into the narrative such generalization and arguments as are warranted by the evidence. This approach I take to be appropriate to the basic argument of this book: that Washington’s inauguration helped instill into the American story a degree of faith in the essential dignity of republican government that we cannot afford to let lapse. I will return to this matter of faith in the conclusion for further comment and offer briefly a set of reflections borne by the journey to Federal Hall.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.